Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

198<br />

Natural and human-made disasters<br />

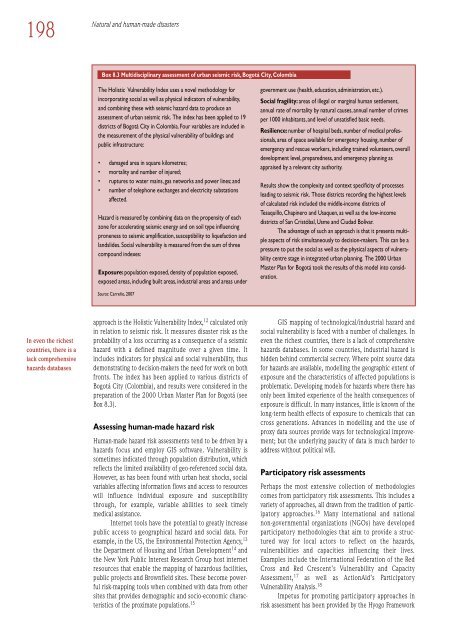

Box 8.3 Multidisciplinary assessment of urban seismic risk, Bogotá City, Colombia<br />

The Holistic Vulnerability Index uses a novel methodology for<br />

incorporating social as well as physical indicators of vulnerability,<br />

and combining these with seismic hazard data to produce an<br />

assessment of urban seismic risk. The index has been applied to 19<br />

districts of Bogotá City in Colombia. Four variables are included in<br />

the measurement of the physical vulnerability of buildings and<br />

public infrastructure:<br />

• damaged area in square kilometres;<br />

• mortality and number of injured;<br />

• ruptures to water mains, gas networks and power lines; and<br />

• number of teleph<strong>on</strong>e exchanges and electricity substati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

affected.<br />

Hazard is measured by combining data <strong>on</strong> the propensity of each<br />

z<strong>on</strong>e for accelerating seismic energy and <strong>on</strong> soil type influencing<br />

pr<strong>on</strong>eness to seismic amplificati<strong>on</strong>, susceptibility to liquefacti<strong>on</strong> and<br />

landslides. Social vulnerability is measured from the sum of three<br />

compound indexes:<br />

Exposure: populati<strong>on</strong> exposed, density of populati<strong>on</strong> exposed,<br />

exposed areas, including built areas, industrial areas and areas under<br />

government use (health, educati<strong>on</strong>, administrati<strong>on</strong>, etc.).<br />

Social fragility: areas of illegal or marginal human settlement,<br />

annual rate of mortality by natural causes, annual number of crimes<br />

per 1000 inhabitants, and level of unsatisfied basic needs.<br />

Resilience: number of hospital beds, number of medical professi<strong>on</strong>als,<br />

area of space available for emergency housing, number of<br />

emergency and rescue workers, including trained volunteers, overall<br />

development level, preparedness, and emergency planning as<br />

appraised by a relevant city authority.<br />

Results show the complexity and c<strong>on</strong>text specificity of processes<br />

leading to seismic risk. Those districts recording the highest levels<br />

of calculated risk included the middle-income districts of<br />

Tesaquillo, Chapinero and Usaquen, as well as the low-income<br />

districts of San Cristóbal, Usme and Ciudad Bolivar.<br />

The advantage of such an approach is that it presents multiple<br />

aspects of risk simultaneously to decisi<strong>on</strong>-makers. This can be a<br />

pressure to put the social as well as the physical aspects of vulnerability<br />

centre stage in integrated urban planning. The 2000 Urban<br />

Master Plan for Bogotá took the results of this model into c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Source: Carreño, <strong>2007</strong><br />

In even the richest<br />

countries, there is a<br />

lack comprehensive<br />

hazards databases<br />

approach is the Holistic Vulnerability Index, 12 calculated <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

in relati<strong>on</strong> to seismic risk. It measures disaster risk as the<br />

probability of a loss occurring as a c<strong>on</strong>sequence of a seismic<br />

hazard with a defined magnitude over a given time. It<br />

includes indicators for physical and social vulnerability, thus<br />

dem<strong>on</strong>strating to decisi<strong>on</strong>-makers the need for work <strong>on</strong> both<br />

fr<strong>on</strong>ts. The index has been applied to various districts of<br />

Bogotá City (Colombia), and results were c<strong>on</strong>sidered in the<br />

preparati<strong>on</strong> of the 2000 Urban Master Plan for Bogotá (see<br />

Box 8.3).<br />

Assessing human-made hazard risk<br />

<strong>Human</strong>-made hazard risk assessments tend to be driven by a<br />

hazards focus and employ GIS software. Vulnerability is<br />

sometimes indicated through populati<strong>on</strong> distributi<strong>on</strong>, which<br />

reflects the limited availability of geo-referenced social data.<br />

However, as has been found with urban heat shocks, social<br />

variables affecting informati<strong>on</strong> flows and access to resources<br />

will influence individual exposure and susceptibility<br />

through, for example, variable abilities to seek timely<br />

medical assistance.<br />

Internet tools have the potential to greatly increase<br />

public access to geographical hazard and social data. For<br />

example, in the US, the Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Protecti<strong>on</strong> Agency, 13<br />

the Department of Housing and Urban Development 14 and<br />

the New York Public Interest Research Group host internet<br />

resources that enable the mapping of hazardous facilities,<br />

public projects and Brownfield sites. These become powerful<br />

risk-mapping tools when combined with data from other<br />

sites that provides demographic and socio-ec<strong>on</strong>omic characteristics<br />

of the proximate populati<strong>on</strong>s. 15<br />

GIS mapping of technological/industrial hazard and<br />

social vulnerability is faced with a number of challenges. In<br />

even the richest countries, there is a lack of comprehensive<br />

hazards databases. In some countries, industrial hazard is<br />

hidden behind commercial secrecy. Where point source data<br />

for hazards are available, modelling the geographic extent of<br />

exposure and the characteristics of affected populati<strong>on</strong>s is<br />

problematic. Developing models for hazards where there has<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly been limited experience of the health c<strong>on</strong>sequences of<br />

exposure is difficult. In many instances, little is known of the<br />

l<strong>on</strong>g-term health effects of exposure to chemicals that can<br />

cross generati<strong>on</strong>s. Advances in modelling and the use of<br />

proxy data sources provide ways for technological improvement;<br />

but the underlying paucity of data is much harder to<br />

address without political will.<br />

Participatory risk assessments<br />

Perhaps the most extensive collecti<strong>on</strong> of methodologies<br />

comes from participatory risk assessments. This includes a<br />

variety of approaches, all drawn from the traditi<strong>on</strong> of participatory<br />

approaches. 16 Many internati<strong>on</strong>al and nati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

n<strong>on</strong>-governmental organizati<strong>on</strong>s (NGOs) have developed<br />

participatory methodologies that aim to provide a structured<br />

way for local actors to reflect <strong>on</strong> the hazards,<br />

vulnerabilities and capacities influencing their lives.<br />

Examples include the Internati<strong>on</strong>al Federati<strong>on</strong> of the Red<br />

Cross and Red Crescent’s Vulnerability and Capacity<br />

Assessment, 17 as well as Acti<strong>on</strong>Aid’s Participatory<br />

Vulnerability Analysis. 18<br />

Impetus for promoting participatory approaches in<br />

risk assessment has been provided by the Hyogo Framework