Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Global Report on Human Settlements 2007 - PoA-ISS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Security of tenure: C<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s and trends<br />

127<br />

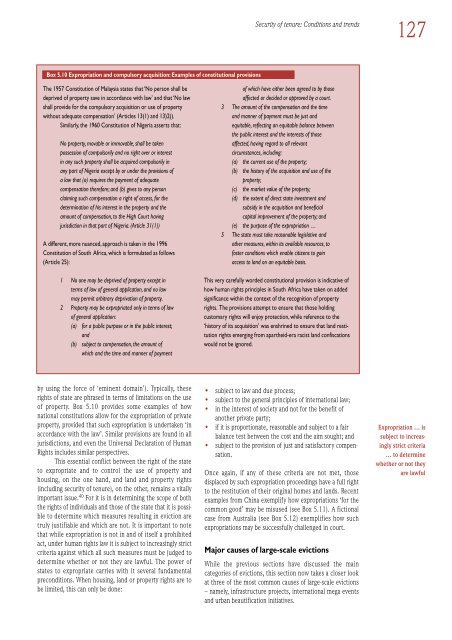

Box 5.10 Expropriati<strong>on</strong> and compulsory acquisiti<strong>on</strong>: Examples of c<strong>on</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al provisi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

The 1957 C<strong>on</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong> of Malaysia states that ‘No pers<strong>on</strong> shall be<br />

deprived of property save in accordance with law’ and that ‘No law<br />

shall provide for the compulsory acquisiti<strong>on</strong> or use of property<br />

without adequate compensati<strong>on</strong>’ (Articles 13(1) and 13)2)).<br />

Similarly, the 1960 C<strong>on</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong> of Nigeria asserts that:<br />

No property, movable or immovable, shall be taken<br />

possessi<strong>on</strong> of compulsorily and no right over or interest<br />

in any such property shall be acquired compulsorily in<br />

any part of Nigeria except by or under the provisi<strong>on</strong>s of<br />

a law that (a) requires the payment of adequate<br />

compensati<strong>on</strong> therefore; and (b) gives to any pers<strong>on</strong><br />

claiming such compensati<strong>on</strong> a right of access, for the<br />

determinati<strong>on</strong> of his interest in the property and the<br />

amount of compensati<strong>on</strong>, to the High Court having<br />

jurisdicti<strong>on</strong> in that part of Nigeria. (Article 31(1))<br />

A different, more nuanced, approach is taken in the 1996<br />

C<strong>on</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong> of South Africa, which is formulated as follows<br />

(Article 25):<br />

1 No <strong>on</strong>e may be deprived of property except in<br />

terms of law of general applicati<strong>on</strong>, and no law<br />

may permit arbitrary deprivati<strong>on</strong> of property.<br />

2 Property may be expropriated <strong>on</strong>ly in terms of law<br />

of general applicati<strong>on</strong>:<br />

(a) for a public purpose or in the public interest;<br />

and<br />

(b) subject to compensati<strong>on</strong>, the amount of<br />

which and the time and manner of payment<br />

of which have either been agreed to by those<br />

affected or decided or approved by a court.<br />

3 The amount of the compensati<strong>on</strong> and the time<br />

and manner of payment must be just and<br />

equitable, reflecting an equitable balance between<br />

the public interest and the interests of those<br />

affected, having regard to all relevant<br />

circumstances, including:<br />

(a) the current use of the property;<br />

(b) the history of the acquisiti<strong>on</strong> and use of the<br />

property;<br />

(c) the market value of the property;<br />

(d) the extent of direct state investment and<br />

subsidy in the acquisiti<strong>on</strong> and beneficial<br />

capital improvement of the property; and<br />

(e) the purpose of the expropriati<strong>on</strong> …<br />

5 The state must take reas<strong>on</strong>able legislative and<br />

other measures, within its available resources, to<br />

foster c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s which enable citizens to gain<br />

access to land <strong>on</strong> an equitable basis.<br />

This very carefully worded c<strong>on</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al provisi<strong>on</strong> is indicative of<br />

how human rights principles in South Africa have taken <strong>on</strong> added<br />

significance within the c<strong>on</strong>text of the recogniti<strong>on</strong> of property<br />

rights. The provisi<strong>on</strong>s attempt to ensure that those holding<br />

customary rights will enjoy protecti<strong>on</strong>, while reference to the<br />

‘history of its acquisiti<strong>on</strong>’ was enshrined to ensure that land restituti<strong>on</strong><br />

rights emerging from apartheid-era racist land c<strong>on</strong>fiscati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

would not be ignored.<br />

by using the force of ‘eminent domain’). Typically, these<br />

rights of state are phrased in terms of limitati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> the use<br />

of property. Box 5.10 provides some examples of how<br />

nati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>s allow for the expropriati<strong>on</strong> of private<br />

property, provided that such expropriati<strong>on</strong> is undertaken ‘in<br />

accordance with the law’. Similar provisi<strong>on</strong>s are found in all<br />

jurisdicti<strong>on</strong>s, and even the Universal Declarati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>Human</strong><br />

Rights includes similar perspectives.<br />

This essential c<strong>on</strong>flict between the right of the state<br />

to expropriate and to c<strong>on</strong>trol the use of property and<br />

housing, <strong>on</strong> the <strong>on</strong>e hand, and land and property rights<br />

(including security of tenure), <strong>on</strong> the other, remains a vitally<br />

important issue. 40 For it is in determining the scope of both<br />

the rights of individuals and those of the state that it is possible<br />

to determine which measures resulting in evicti<strong>on</strong> are<br />

truly justifiable and which are not. It is important to note<br />

that while expropriati<strong>on</strong> is not in and of itself a prohibited<br />

act, under human rights law it is subject to increasingly strict<br />

criteria against which all such measures must be judged to<br />

determine whether or not they are lawful. The power of<br />

states to expropriate carries with it several fundamental<br />

prec<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. When housing, land or property rights are to<br />

be limited, this can <strong>on</strong>ly be d<strong>on</strong>e:<br />

• subject to law and due process;<br />

• subject to the general principles of internati<strong>on</strong>al law;<br />

• in the interest of society and not for the benefit of<br />

another private party;<br />

• if it is proporti<strong>on</strong>ate, reas<strong>on</strong>able and subject to a fair<br />

balance test between the cost and the aim sought; and<br />

• subject to the provisi<strong>on</strong> of just and satisfactory compensati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Once again, if any of these criteria are not met, those<br />

displaced by such expropriati<strong>on</strong> proceedings have a full right<br />

to the restituti<strong>on</strong> of their original homes and lands. Recent<br />

examples from China exemplify how expropriati<strong>on</strong>s ‘for the<br />

comm<strong>on</strong> good’ may be misused (see Box 5.11). A ficti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

case from Australia (see Box 5.12) exemplifies how such<br />

expropriati<strong>on</strong>s may be successfully challenged in court.<br />

Major causes of large-scale evicti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

While the previous secti<strong>on</strong>s have discussed the main<br />

categories of evicti<strong>on</strong>s, this secti<strong>on</strong> now takes a closer look<br />

at three of the most comm<strong>on</strong> causes of large-scale evicti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

– namely, infrastructure projects, internati<strong>on</strong>al mega events<br />

and urban beautificati<strong>on</strong> initiatives.<br />

Expropriati<strong>on</strong> … is<br />

subject to increasingly<br />

strict criteria<br />

… to determine<br />

whether or not they<br />

are lawful