SOU OBà DùJINY - Ãstav pro soudobé dÄjiny AV - Akademie vÄd ÄR

SOU OBà DùJINY - Ãstav pro soudobé dÄjiny AV - Akademie vÄd ÄR

SOU OBà DùJINY - Ãstav pro soudobé dÄjiny AV - Akademie vÄd ÄR

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

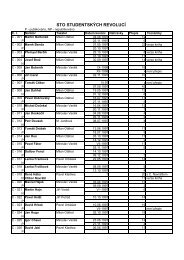

244 Soudobé dějiny XIV / 1Students were clearly predominant amongst them. Most of the Belarusians inCzechoslovakia (about a hundred people) were involved in the national movement.Since, however, the émigrés <strong>pro</strong>bably did not manage to achieve de facto recognition,Belarusian national life could develop in Czechoslovakia only by means of clubs. Interms of politics, their situation was similar to that of the Russians’ and Ukrainians’situation in Czechoslovakia: a heterogeneous group, which included ChristianDemocrats, Socialist-Revolutionaries, and Socialists. Soviet diplomats and secretagents were agitating amongst them with growing success. Only a minimum ofBelarusians were oriented to working with Russian émigrés. Apart from havinga political side, the club life of Belarusian students in Czechoslovakia also involvedthe arts. It failed, however, to create an independent Belarusian scholarly institution.Ultimately, the departure of students to find work in Belarusian parts of Poland,together with the consequences of the Great Depression, led to the failure of theBelarusian movement in Czechoslovakia. The Belarusian Self-help Committee’sloyalty to the German authorities after the Occupation of Bohemia and Moravia castthe Belarusian national movement here into doubt amongst people opposed to theGerman Reich. This chapter of Czech-Belarusian relations closes with the handingoverof Belarusian émigrés to the Soviet authorities after the Second World War. Asa supplement to the article the author <strong>pro</strong>vides biographical sketches of a hundredimportant Belarusian émigrés in Czechoslovakia.HorizonToo Many Nazis? Contemporary History in Great BritainDetlev MaresThis is a translation of the article “Too Many Nazis? Zeitgeschichte in Großbritannien”originally published in Alexander Nützenadel and Wolfgang Schieder (eds)Zeitgeschichte als Problem: Nationale Traditionen und Perspektiven der Forschung inEuropa (Göttingen, 2004). According to the author contemporary history in GreatBritain begins in the period just after the Second World War, when the public ingeneral and historians began to ask questions about the causes of the war and soughtcritically to come to terms with the pre-war policy of appeasement. (Nazism itself hascontinued to be a frequent topic of research in Great Britain.) In terms of institutions,however, the field did not begin to develop till the mid-1960s, when the Instituteof Contemporary History and, with it, the Journal of Contemporary History werefounded. Historians of contemporary history initially had <strong>pro</strong>blems, of course, gettingthe new field accepted amongst their “traditionally” oriented colleagues; apart fromthe usual objection concerning the allegedly insufficient amount of time having passedsince the event being researched took place, they have struggled with the somewhatparadoxical <strong>pro</strong>blem that, unlike countries on the Continent, twentieth-century GreatBritain did not experience any radical historical break in continuity. Today the field