2294 part 1 final report.pdf - Agra CEAS Consulting

2294 part 1 final report.pdf - Agra CEAS Consulting

2294 part 1 final report.pdf - Agra CEAS Consulting

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

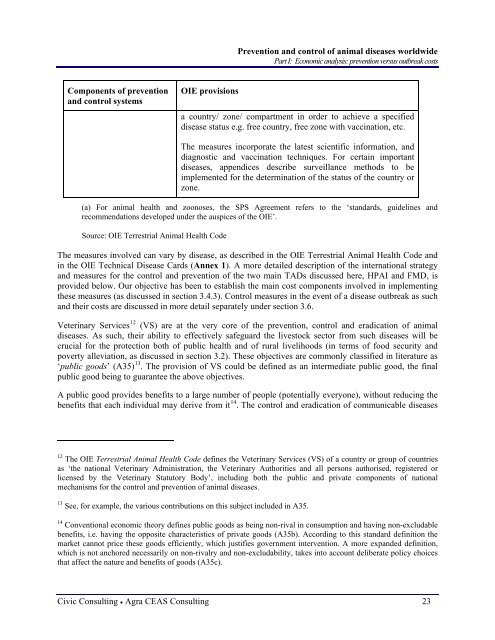

Prevention and control of animal diseases worldwide<br />

Part I: Economic analysis: prevention versus outbreak costs<br />

Components of prevention<br />

and control systems<br />

OIE provisions<br />

a country/ zone/ com<strong>part</strong>ment in order to achieve a specified<br />

disease status e.g. free country, free zone with vaccination, etc.<br />

The measures incorporate the latest scientific information, and<br />

diagnostic and vaccination techniques. For certain important<br />

diseases, appendices describe surveillance methods to be<br />

implemented for the determination of the status of the country or<br />

zone.<br />

(a) For animal health and zoonoses, the SPS Agreement refers to the ‘standards, guidelines and<br />

recommendations developed under the auspices of the OIE’.<br />

Source: OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code<br />

The measures involved can vary by disease, as described in the OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code and<br />

in the OIE Technical Disease Cards (Annex 1). A more detailed description of the international strategy<br />

and measures for the control and prevention of the two main TADs discussed here, HPAI and FMD, is<br />

provided below. Our objective has been to establish the main cost components involved in implementing<br />

these measures (as discussed in section 3.4.3). Control measures in the event of a disease outbreak as such<br />

and their costs are discussed in more detail separately under section 3.6.<br />

Veterinary Services 12 (VS) are at the very core of the prevention, control and eradication of animal<br />

diseases. As such, their ability to effectively safeguard the livestock sector from such diseases will be<br />

crucial for the protection both of public health and of rural livelihoods (in terms of food security and<br />

poverty alleviation, as discussed in section 3.2). These objectives are commonly classified in literature as<br />

‘public goods’ (A35) 13 . The provision of VS could be defined as an intermediate public good, the <strong>final</strong><br />

public good being to guarantee the above objectives.<br />

A public good provides benefits to a large number of people (potentially everyone), without reducing the<br />

benefits that each individual may derive from it 14 . The control and eradication of communicable diseases<br />

12 The OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code defines the Veterinary Services (VS) of a country or group of countries<br />

as ‘the national Veterinary Administration, the Veterinary Authorities and all persons authorised, registered or<br />

licensed by the Veterinary Statutory Body’, including both the public and private components of national<br />

mechanisms for the control and prevention of animal diseases.<br />

13 See, for example, the various contributions on this subject included in A35.<br />

14 Conventional economic theory defines public goods as being non-rival in consumption and having non-excludable<br />

benefits, i.e. having the opposite characteristics of private goods (A35b). According to this standard definition the<br />

market cannot price these goods efficiently, which justifies government intervention. A more expanded definition,<br />

which is not anchored necessarily on non-rivalry and non-excludability, takes into account deliberate policy choices<br />

that affect the nature and benefits of goods (A35c).<br />

Civic <strong>Consulting</strong> • <strong>Agra</strong> <strong>CEAS</strong> <strong>Consulting</strong> 23