Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

showing that the proposition to be demonstrated is an identical proposition, the certainty<br />

of which requires no further demonstration—nor can one be given. The certainty does not<br />

rest on “self-evidence” as Locke claims, since the proposition depends on more-basic<br />

truths. This is a model of demonstration in the strictest sense. No other type of<br />

demonstration comes this close to following the strict requirements of demonstration, i.e.,<br />

reducing all terms and propositions to identities.<br />

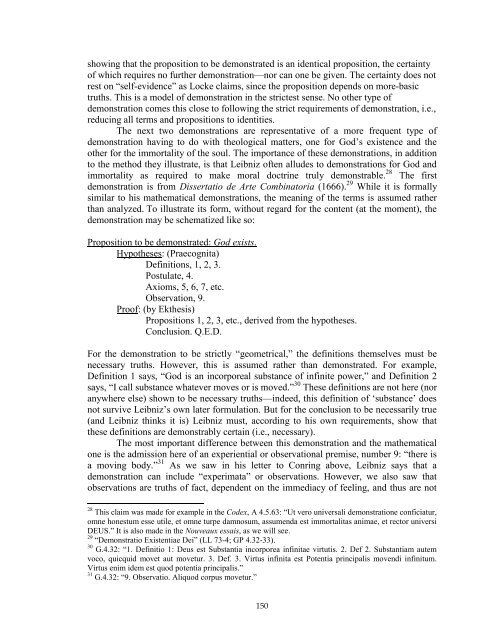

The next two demonstrations are representative of a more frequent type of<br />

demonstration having to do with theological matters, one for God’s existence and the<br />

other for the immortality of the soul. The importance of these demonstrations, in addition<br />

to the method they illustrate, is that Leibniz often alludes to demonstrations for God and<br />

immortality as required to make moral doctrine truly demonstrable. 28 The first<br />

demonstration is from Dissertatio de Arte Combinatoria (1666). 29 While it is formally<br />

similar to his mathematical demonstrations, the meaning of the terms is assumed rather<br />

than analyzed. To illustrate its form, without regard for the content (at the moment), the<br />

demonstration may be schematized like so:<br />

Proposition to be demonstrated: God exists.<br />

Hypotheses: (Praecognita)<br />

Definitions, 1, 2, 3.<br />

Postulate, 4.<br />

Axioms, 5, 6, 7, etc.<br />

Observation, 9.<br />

Proof: (by Ekthesis)<br />

Propositions 1, 2, 3, etc., derived from the hypotheses.<br />

Conclusion. Q.E.D.<br />

For the demonstration to be strictly “geometrical,” the definitions themselves must be<br />

necessary truths. However, this is assumed rather than demonstrated. For example,<br />

Definition 1 says, “God is an incorporeal substance of infinite power,” and Definition 2<br />

says, “I call substance whatever moves or is moved.” 30 These definitions are not here (nor<br />

anywhere else) shown to be necessary truths—indeed, this definition of ‘substance’ does<br />

not survive Leibniz’s own later formulation. But for the conclusion to be necessarily true<br />

(and Leibniz thinks it is) Leibniz must, according to his own requirements, show that<br />

these definitions are demonstrably certain (i.e., necessary).<br />

The most important difference between this demonstration and the mathematical<br />

one is the admission here of an experiential or observational premise, number 9: “there is<br />

a moving body.” 31 As we saw in his letter to Conring above, Leibniz says that a<br />

demonstration can include “experimata” or observations. However, we also saw that<br />

observations are truths of fact, dependent on the immediacy of feeling, and thus are not<br />

28 This claim was made for example in the Codex, A 4.5.63: “Ut vero universali demonstratione conficiatur,<br />

omne honestum esse utile, et omne turpe damnosum, assumenda est immortalitas animae, et rector universi<br />

DEUS.” It is also made in the Nouveaux essais, as we will see.<br />

29 “Demonstratio Existentiae Dei” (LL 73-4; GP 4.32-33).<br />

30 G.4.32: “1. Definitio 1: Deus est Substantia incorporea infinitae virtutis. 2. Def 2. Substantiam autem<br />

voco, quicquid movet aut movetur. 3. Def. 3. Virtus infinita est Potentia principalis movendi infinitum.<br />

Virtus enim idem est quod potentia principalis.”<br />

31 G.4.32: “9. Observatio. Aliquod corpus movetur.”<br />

150