Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

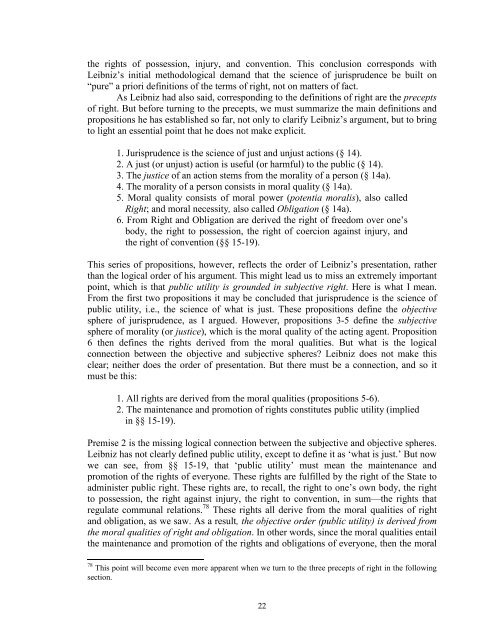

the rights of possession, injury, and convention. This conclusion corresponds with<br />

Leibniz’s initial methodological demand that the science of jurisprudence be built on<br />

“pure” a priori definitions of the terms of right, not on matters of fact.<br />

As Leibniz had also said, corresponding to the definitions of right are the precepts<br />

of right. But before turning to the precepts, we must summarize the main definitions and<br />

propositions he has established so far, not only to clarify Leibniz’s argument, but to bring<br />

to light an essential point that he does not make explicit.<br />

1. Jurisprudence is the science of just and unjust actions (§ 14).<br />

2. A just (or unjust) action is useful (or harmful) to the public (§ 14).<br />

3. The justice of an action stems from the morality of a person (§ 14a).<br />

4. The morality of a person consists in moral quality (§ 14a).<br />

5. Moral quality consists of moral power (potentia moralis), also called<br />

Right; and moral necessity, also called Obligation (§ 14a).<br />

6. From Right and Obligation are derived the right of freedom over one’s<br />

body, the right to possession, the right of coercion against injury, and<br />

the right of convention (§§ 15-19).<br />

This series of propositions, however, reflects the order of Leibniz’s presentation, rather<br />

than the logical order of his argument. This might lead us to miss an extremely important<br />

point, which is that public utility is grounded in subjective right. Here is what I mean.<br />

From the first two propositions it may be concluded that jurisprudence is the science of<br />

public utility, i.e., the science of what is just. These propositions define the objective<br />

sphere of jurisprudence, as I argued. However, propositions 3-5 define the subjective<br />

sphere of morality (or justice), which is the moral quality of the acting agent. Proposition<br />

6 then defines the rights derived from the moral qualities. But what is the logical<br />

connection between the objective and subjective spheres? Leibniz does not make this<br />

clear; neither does the order of presentation. But there must be a connection, and so it<br />

must be this:<br />

1. All rights are derived from the moral qualities (propositions 5-6).<br />

2. The maintenance and promotion of rights constitutes public utility (implied<br />

in §§ 15-19).<br />

Premise 2 is the missing logical connection between the subjective and objective spheres.<br />

Leibniz has not clearly defined public utility, except to define it as ‘what is just.’ But now<br />

we can see, from §§ 15-19, that ‘public utility’ must mean the maintenance and<br />

promotion of the rights of everyone. These rights are fulfilled by the right of the State to<br />

administer public right. These rights are, to recall, the right to one’s own body, the right<br />

to possession, the right against injury, the right to convention, in sum—the rights that<br />

regulate communal relations. 78 These rights all derive from the moral qualities of right<br />

and obligation, as we saw. As a result, the objective order (public utility) is derived from<br />

the moral qualities of right and obligation. In other words, since the moral qualities entail<br />

the maintenance and promotion of the rights and obligations of everyone, then the moral<br />

78 This point will become even more apparent when we turn to the three precepts of right in the following<br />

section.<br />

22