Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

notion of probability, which they have confused with Aristotle’s endoxon<br />

or acceptability. (NE 372) 68<br />

Leibniz adds that arguments from probability are drawn from the nature of things, not<br />

from acceptability. Just as stronger evidence in scientific experiments improves the<br />

likelihood that the conclusions are true, the weight of reasons can provide the probability,<br />

or presumptive validity, that our moral judgments are correct. “I suspect that<br />

establishment of an art of estimating likelihoods would be more useful than a good<br />

portion of our demonstrative sciences, and I have more than once contemplated it” (NE<br />

373). Presumably, the same holds for moral questions. This is an interesting and<br />

undeveloped aspect of Leibniz’s moral thinking, but we will not pursue it here.<br />

Section 6: Did Leibniz demonstrate the proposition ‘justice is the charity of the<br />

wise’?<br />

We have seen how Leibniz thought that a definition could not be a real definition<br />

unless it was shown to be possible. This essentially means showing that the definition<br />

contains no internal inconsistency. To do this requires that the terms of a proposition be<br />

analyzed through a continuous substitution of definitions, i.e., a definition chain. The<br />

terms of definition A are defined by B; B is defined by C; C is defined by D, and so forth.<br />

The longest and possibly the most exhaustive of definition chains begins with the<br />

definition of the vir bonus, as we have seen.<br />

While this method is rigorous, the main drawback is that we are uncertain when a<br />

primitive concept is reached. And there is no indication of what the primitive concepts<br />

are. Nevertheless, this method can certainly bring to light the content of definitions,<br />

reveal their internal consistency (or inconsistency) and expose the other concepts related<br />

to it. It is appropriate then to examine the definition chain that begins with the definition<br />

of justice as charity of the wise. As we saw, this definition is widely recognized as<br />

Leibniz’s mature and complete definition of justice; although, it has not been shown<br />

whether it conforms to Leibniz’s demonstrative method. Does the definition contain real<br />

possibility? Internal inconsistency? Primitive concepts? Is it an a priori definition? The<br />

following is Leibniz’s own German version of the Latin version we saw in Chapter Three<br />

(from 1678-9):<br />

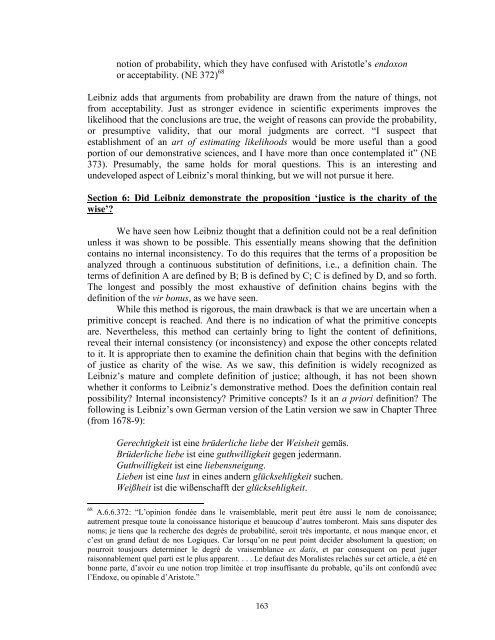

Gerechtigkeit ist eine brüderliche liebe der Weisheit gemäs.<br />

Brüderliche liebe ist eine guthwilligkeit gegen jedermann.<br />

Guthwilligkeit ist eine liebensneigung.<br />

Lieben ist eine lust in eines andern glücksehligkeit suchen.<br />

Weißheit ist die wißenschafft der glücksehligkeit.<br />

68 A.6.6.372: “L’opinion fondée dans le vraisemblable, merit peut être aussi le nom de conoissance;<br />

autrement presque toute la conoissance historique et beaucoup d’autres tomberont. Mais sans disputer des<br />

noms; je tiens que la recherche des degrés de probabilité, seroit trés importante, et nous manque encor, et<br />

c’est un grand defaut de nos Logiques. Car lorsqu’on ne peut point decider absolument la question; on<br />

pourroit tousjours determiner le degré de vraisemblance ex datis, et par consequent on peut juger<br />

raisonnablement quel parti est le plus apparent. . . . Le defaut des Moralistes relachés sur cet article, a été en<br />

bonne parte, d’avoir eu une notion trop limitée et trop insuffisante du probable, qu’ils ont confondû avec<br />

l’Endoxe, ou opinable d’Aristote.”<br />

163