Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University

Stony Brook University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

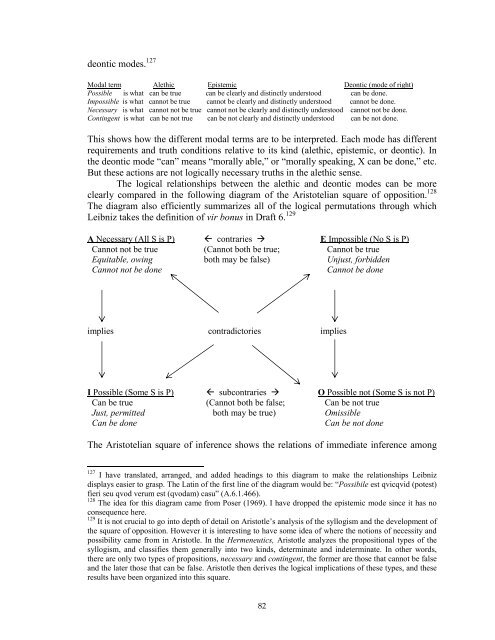

deontic modes. 127<br />

Modal term Alethic Epistemic Deontic (mode of right)<br />

Possible is what can be true can be clearly and distinctly understood can be done.<br />

Impossible is what cannot be true cannot be clearly and distinctly understood cannot be done.<br />

Necessary is what cannot not be true cannot not be clearly and distinctly understood cannot not be done.<br />

Contingent is what can be not true can be not clearly and distinctly understood can be not done.<br />

This shows how the different modal terms are to be interpreted. Each mode has different<br />

requirements and truth conditions relative to its kind (alethic, epistemic, or deontic). In<br />

the deontic mode “can” means “morally able,” or “morally speaking, X can be done,” etc.<br />

But these actions are not logically necessary truths in the alethic sense.<br />

The logical relationships between the alethic and deontic modes can be more<br />

clearly compared in the following diagram of the Aristotelian square of opposition. 128<br />

The diagram also efficiently summarizes all of the logical permutations through which<br />

Leibniz takes the definition of vir bonus in Draft 6. 129<br />

A Necessary (All S is P) contraries E Impossible (No S is P)<br />

Cannot not be true (Cannot both be true; Cannot be true<br />

Equitable, owing both may be false) Unjust, forbidden<br />

Cannot not be done Cannot be done<br />

implies contradictories implies<br />

I Possible (Some S is P) subcontraries O Possible not (Some S is not P)<br />

Can be true (Cannot both be false; Can be not true<br />

Just, permitted both may be true) Omissible<br />

Can be done Can be not done<br />

The Aristotelian square of inference shows the relations of immediate inference among<br />

127<br />

I have translated, arranged, and added headings to this diagram to make the relationships Leibniz<br />

displays easier to grasp. The Latin of the first line of the diagram would be: “Possibile est qvicqvid (potest)<br />

fieri seu qvod verum est (qvodam) casu” (A.6.1.466).<br />

128<br />

The idea for this diagram came from Poser (1969). I have dropped the epistemic mode since it has no<br />

consequence here.<br />

129<br />

It is not crucial to go into depth of detail on Aristotle’s analysis of the syllogism and the development of<br />

the square of opposition. However it is interesting to have some idea of where the notions of necessity and<br />

possibility came from in Aristotle. In the Hermeneutics, Aristotle analyzes the propositional types of the<br />

syllogism, and classifies them generally into two kinds, determinate and indeterminate. In other words,<br />

there are only two types of propositions, necessary and contingent, the former are those that cannot be false<br />

and the later those that can be false. Aristotle then derives the logical implications of these types, and these<br />

results have been organized into this square.<br />

82