Reduction and Elimination in Philosophy and the Sciences

Reduction and Elimination in Philosophy and the Sciences

Reduction and Elimination in Philosophy and the Sciences

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

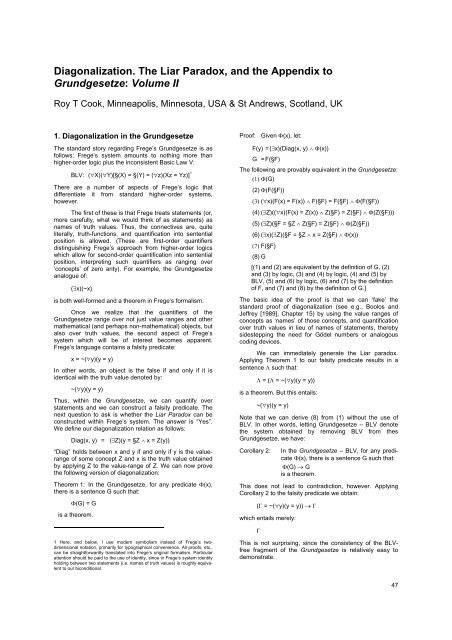

Diagonalization. The Liar Paradox, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Appendix to<br />

Grundgesetze: Volume II<br />

Roy T Cook, M<strong>in</strong>neapolis, M<strong>in</strong>nesota, USA & St Andrews, Scotl<strong>and</strong>, UK<br />

1. Diagonalization <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Grundgesetze<br />

The st<strong>and</strong>ard story regard<strong>in</strong>g Frege’s Grundgesetze is as<br />

follows: Frege’s system amounts to noth<strong>in</strong>g more than<br />

higher-order logic plus <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>consistent Basic Law V:<br />

BLV: (∀X)(∀Y)[§(X) = §(Y) = (∀z)(Xz = Yz)] 1<br />

There are a number of aspects of Frege’s logic that<br />

differentiate it from st<strong>and</strong>ard higher-order systems,<br />

however.<br />

The first of <strong>the</strong>se is that Frege treats statements (or,<br />

more carefully, what we would th<strong>in</strong>k of as statements) as<br />

names of truth values. Thus, <strong>the</strong> connectives are, quite<br />

literally, truth-functions, <strong>and</strong> quantification <strong>in</strong>to sentential<br />

position is allowed. (These are first-order quantifiers<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g Frege’s approach from higher-order logics<br />

which allow for second-order quantification <strong>in</strong>to sentential<br />

position, <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g such quantifiers as rang<strong>in</strong>g over<br />

‘concepts’ of zero arity). For example, <strong>the</strong> Grundgesetze<br />

analogue of:<br />

(∃x)(~x)<br />

is both well-formed <strong>and</strong> a <strong>the</strong>orem <strong>in</strong> Frege’s formalism.<br />

Once we realize that <strong>the</strong> quantifiers of <strong>the</strong><br />

Grundgesetze range over not just value ranges <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

ma<strong>the</strong>matical (<strong>and</strong> perhaps non-ma<strong>the</strong>matical) objects, but<br />

also over truth values, <strong>the</strong> second aspect of Frege’s<br />

system which will be of <strong>in</strong>terest becomes apparent.<br />

Frege’s language conta<strong>in</strong>s a falsity predicate:<br />

x = ~(∀y)(y = y)<br />

In o<strong>the</strong>r words, an object is <strong>the</strong> false if <strong>and</strong> only if it is<br />

identical with <strong>the</strong> truth value denoted by:<br />

~(∀y)(y = y)<br />

Thus, with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Grundgesetze, we can quantify over<br />

statements <strong>and</strong> we can construct a falsity predicate. The<br />

next question to ask is whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Liar Paradox can be<br />

constructed with<strong>in</strong> Frege’s system. The answer is “Yes”.<br />

We def<strong>in</strong>e our diagonalization relation as follows:<br />

Diag(x, y) = (∃Z)(y = §Z ∧ x = Z(y))<br />

“Diag” holds between x <strong>and</strong> y if <strong>and</strong> only if y is <strong>the</strong> valuerange<br />

of some concept Z <strong>and</strong> x is <strong>the</strong> truth value obta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

by apply<strong>in</strong>g Z to <strong>the</strong> value-range of Z. We can now prove<br />

<strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g version of diagonalization:<br />

Theorem 1: In <strong>the</strong> Grundgesetze, for any predicate Φ(x),<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is a sentence G such that:<br />

Φ(G) = G<br />

is a <strong>the</strong>orem.<br />

1 Here, <strong>and</strong> below, I use modern symbolism <strong>in</strong>stead of Frege’s twodimensional<br />

notation, primarily for typographical convenience. All proofs, etc.,<br />

can be straightforwardly translated <strong>in</strong>to Frege’s orig<strong>in</strong>al formalism. Particular<br />

attention should be paid to <strong>the</strong> use of identity, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong> Frege’s system identity<br />

hold<strong>in</strong>g between two statements (i.e. names of truth values) is roughly equivalent<br />

to our biconditional.<br />

Proof: Given Φ(x), let:<br />

F(y) = (∃x)(Diag(x, y) ∧ Φ(x))<br />

G = F(§F)<br />

The follow<strong>in</strong>g are provably equivalent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Grundgesetze:<br />

(1) Φ(G)<br />

(2) Φ(F(§F))<br />

(3) (∀x)(F(x) = F(x)) ∧ F(§F) = F(§F) ∧ Φ(F(§F))<br />

(4) (∃Z)((∀x)(F(x) = Z(x)) ∧ Z(§F) = Z(§F) ∧ Φ(Z(§F)))<br />

(5) (∃Z)(§F = §Z ∧ Z(§F) = Z(§F) ∧ Φ(Z(§F))<br />

(6) (∃x)(∃Z)(§F = §Z ∧ x = Z(§F) ∧ Φ(x))<br />

(7) F(§F)<br />

(8) G<br />

[(1) <strong>and</strong> (2) are equivalent by <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition of G, (2)<br />

<strong>and</strong> (3) by logic, (3) <strong>and</strong> (4) by logic, (4) <strong>and</strong> (5) by<br />

BLV, (5) <strong>and</strong> (6) by logic, (6) <strong>and</strong> (7) by <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition<br />

of F, <strong>and</strong> (7) <strong>and</strong> (8) by <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition of G.]<br />

The basic idea of <strong>the</strong> proof is that we can ‘fake’ <strong>the</strong><br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard proof of diagonalization (see e.g., Boolos <strong>and</strong><br />

Jeffrey [1989], Chapter 15) by us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> value ranges of<br />

concepts as ‘names’ of those concepts, <strong>and</strong> quantification<br />

over truth values <strong>in</strong> lieu of names of statements, <strong>the</strong>reby<br />

sidestepp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> need for Gödel numbers or analogous<br />

cod<strong>in</strong>g devices.<br />

We can immediately generate <strong>the</strong> Liar paradox.<br />

Apply<strong>in</strong>g Theorem 1 to our falsity predicate results <strong>in</strong> a<br />

sentence Λ such that:<br />

Λ = (Λ = ~(∀y)(y = y))<br />

is a <strong>the</strong>orem. But this entails:<br />

~(∀y)(y = y)<br />

Note that we can derive (8) from (1) without <strong>the</strong> use of<br />

BLV. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, lett<strong>in</strong>g Grundgesetze – BLV denote<br />

<strong>the</strong> system obta<strong>in</strong>ed by remov<strong>in</strong>g BLV from <strong>the</strong>s<br />

Grundgesetze, we have:<br />

Corollary 2: In <strong>the</strong> Grundgesetze – BLV, for any predicate<br />

Φ(x), <strong>the</strong>re is a sentence G such that:<br />

Φ(G) → G<br />

is a <strong>the</strong>orem.<br />

This does not lead to contradiction, however. Apply<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Corollary 2 to <strong>the</strong> falsity predicate we obta<strong>in</strong>:<br />

(Γ = ~(∀y)(y = y)) → Γ<br />

which entails merely:<br />

Γ<br />

This is not surpris<strong>in</strong>g, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> consistency of <strong>the</strong> BLVfree<br />

fragment of <strong>the</strong> Grundgesetze is relatively easy to<br />

demonstrate.<br />

47