Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

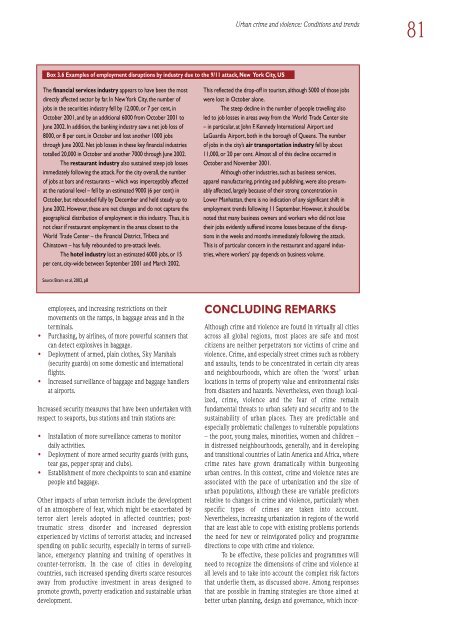

Urban crime and violence: Conditions and trends81Box 3.6 Examples <strong>of</strong> employment disruptions by industry due to <strong>the</strong> 9/11 attack, New York City, USThe financial services industry appears to have been <strong>the</strong> mostdirectly affected sector by far. In New York City, <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong>jobs in <strong>the</strong> securities industry fell by 12,000, or 7 per cent, inOctober 2001, and by an additional 6000 from October 2001 toJune 2002. In addition, <strong>the</strong> banking industry saw a net job loss <strong>of</strong>8000, or 8 per cent, in October and lost ano<strong>the</strong>r 1000 jobsthrough June 2002. Net job losses in <strong>the</strong>se key financial industriestotalled 20,000 in October and ano<strong>the</strong>r 7000 through June 2002.The restaurant industry also sustained steep job lossesimmediately following <strong>the</strong> attack. For <strong>the</strong> city overall, <strong>the</strong> number<strong>of</strong> jobs at bars and restaurants – which was imperceptibly affectedat <strong>the</strong> national level – fell by an estimated 9000 (6 per cent) inOctober, but rebounded fully by December and held steady up toJune 2002. However, <strong>the</strong>se are net changes and do not capture <strong>the</strong>geographical distribution <strong>of</strong> employment in this industry. Thus, it isnot clear if restaurant employment in <strong>the</strong> areas closest to <strong>the</strong>World Trade Center – <strong>the</strong> Financial District, Tribeca andChinatown – has fully rebounded to pre-attack levels.The hotel industry lost an estimated 6000 jobs, or 15per cent, city-wide between September 2001 and March 2002.This reflected <strong>the</strong> drop-<strong>of</strong>f in tourism, although 5000 <strong>of</strong> those jobswere lost in October alone.The steep decline in <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> people travelling alsoled to job losses in areas away from <strong>the</strong> World Trade Center site– in particular, at John F. Kennedy International Airport andLaGuardia Airport, both in <strong>the</strong> borough <strong>of</strong> Queens. The number<strong>of</strong> jobs in <strong>the</strong> city’s air transportation industry fell by about11,000, or 20 per cent. Almost all <strong>of</strong> this decline occurred inOctober and November 2001.Although o<strong>the</strong>r industries, such as business services,apparel manufacturing, printing and publishing, were also presumablyaffected, largely because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir strong concentration inLower Manhattan, <strong>the</strong>re is no indication <strong>of</strong> any significant shift inemployment trends following 11 September. However, it should benoted that many business owners and workers who did not lose<strong>the</strong>ir jobs evidently suffered income losses because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> disruptionsin <strong>the</strong> weeks and months immediately following <strong>the</strong> attack.This is <strong>of</strong> particular concern in <strong>the</strong> restaurant and apparel industries,where workers’ pay depends on business volume.Source: Bram et al, 2002, p8employees, and increasing restrictions on <strong>the</strong>irmovements on <strong>the</strong> ramps, in baggage areas and in <strong>the</strong>terminals.• Purchasing, by airlines, <strong>of</strong> more powerful scanners thatcan detect explosives in baggage.• Deployment <strong>of</strong> armed, plain clo<strong>the</strong>s, Sky Marshals(security guards) on some domestic and internationalflights.• Increased surveillance <strong>of</strong> baggage and baggage handlersat airports.Increased security measures that have been undertaken withrespect to seaports, bus stations and train stations are:• Installation <strong>of</strong> more surveillance cameras to monitordaily activities.• Deployment <strong>of</strong> more armed security guards (with guns,tear gas, pepper spray and clubs).• Establishment <strong>of</strong> more checkpoints to scan and examinepeople and baggage.O<strong>the</strong>r impacts <strong>of</strong> urban terrorism include <strong>the</strong> development<strong>of</strong> an atmosphere <strong>of</strong> fear, which might be exacerbated byterror alert levels adopted in affected countries; posttraumaticstress disorder and increased depressionexperienced by victims <strong>of</strong> terrorist attacks; and increasedspending on public security, especially in terms <strong>of</strong> surveillance,emergency planning and training <strong>of</strong> operatives incounter-terrorism. In <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> cities in developingcountries, such increased spending diverts scarce resourcesaway from productive investment in areas designed topromote growth, poverty eradication and sustainable urbandevelopment.CONCLUDING REMARKSAlthough crime and violence are found in virtually all citiesacross all global regions, most places are safe and mostcitizens are nei<strong>the</strong>r perpetrators nor victims <strong>of</strong> crime andviolence. Crime, and especially street crimes such as robberyand assaults, tends to be concentrated in certain city areasand neighbourhoods, which are <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>the</strong> ‘worst’ urbanlocations in terms <strong>of</strong> property value and environmental risksfrom disasters and hazards. Never<strong>the</strong>less, even though localized,crime, violence and <strong>the</strong> fear <strong>of</strong> crime remainfundamental threats to urban safety and security and to <strong>the</strong>sustainability <strong>of</strong> urban places. They are predictable andespecially problematic challenges to vulnerable populations– <strong>the</strong> poor, young males, minorities, women and children –in distressed neighbourhoods, generally, and in developingand transitional countries <strong>of</strong> Latin America and Africa, wherecrime rates have grown dramatically within burgeoningurban centres. In this context, crime and violence rates areassociated with <strong>the</strong> pace <strong>of</strong> urbanization and <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong>urban populations, although <strong>the</strong>se are variable predictorsrelative to changes in crime and violence, particularly whenspecific types <strong>of</strong> crimes are taken into account.Never<strong>the</strong>less, increasing urbanization in regions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> worldthat are least able to cope with existing problems portends<strong>the</strong> need for new or reinvigorated policy and programmedirections to cope with crime and violence.To be effective, <strong>the</strong>se policies and programmes willneed to recognize <strong>the</strong> dimensions <strong>of</strong> crime and violence atall levels and to take into account <strong>the</strong> complex risk factorsthat underlie <strong>the</strong>m, as discussed above. Among responsesthat are possible in framing strategies are those aimed atbetter urban planning, design and governance, which incor-