Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

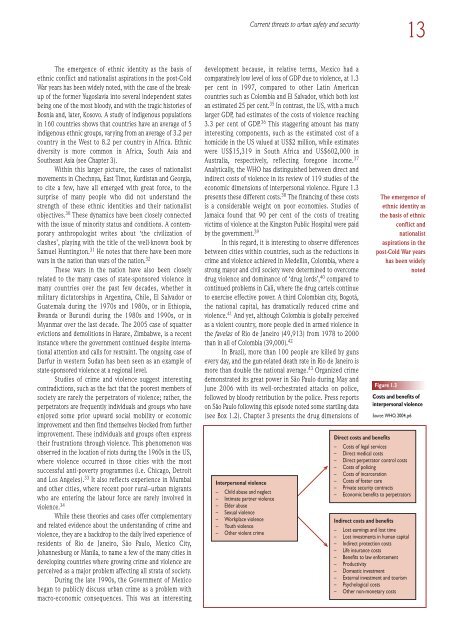

Current threats to urban safety and security13The emergence <strong>of</strong> ethnic identity as <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong>ethnic conflict and nationalist aspirations in <strong>the</strong> post-ColdWar years has been widely noted, with <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> breakup<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> former Yugoslavia into several independent statesbeing one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most bloody, and with <strong>the</strong> tragic histories <strong>of</strong>Bosnia and, later, Kosovo. A study <strong>of</strong> indigenous populationsin 160 countries shows that countries have an average <strong>of</strong> 5indigenous ethnic groups, varying from an average <strong>of</strong> 3.2 percountry in <strong>the</strong> West to 8.2 per country in Africa. Ethnicdiversity is more common in Africa, South Asia andSou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia (see Chapter 3).Within this larger picture, <strong>the</strong> cases <strong>of</strong> nationalistmovements in Chechnya, East Timor, Kurdistan and Georgia,to cite a few, have all emerged with great force, to <strong>the</strong>surprise <strong>of</strong> many people who did not understand <strong>the</strong>strength <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se ethnic identities and <strong>the</strong>ir nationalistobjectives. 30 These dynamics have been closely connectedwith <strong>the</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> minority status and conditions. A contemporaryanthropologist writes about ‘<strong>the</strong> civilization <strong>of</strong>clashes’, playing with <strong>the</strong> title <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> well-known book bySamuel Huntington. 31 He notes that <strong>the</strong>re have been morewars in <strong>the</strong> nation than wars <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nation. 32These wars in <strong>the</strong> nation have also been closelyrelated to <strong>the</strong> many cases <strong>of</strong> state-sponsored violence inmany countries over <strong>the</strong> past few decades, whe<strong>the</strong>r inmilitary dictatorships in Argentina, Chile, El Salvador orGuatemala during <strong>the</strong> 1970s and 1980s, or in Ethiopia,Rwanda or Burundi during <strong>the</strong> 1980s and 1990s, or inMyanmar over <strong>the</strong> last decade. The 2005 case <strong>of</strong> squatterevictions and demolitions in Harare, Zimbabwe, is a recentinstance where <strong>the</strong> government continued despite internationalattention and calls for restraint. The ongoing case <strong>of</strong>Darfur in western Sudan has been seen as an example <strong>of</strong>state-sponsored violence at a regional level.Studies <strong>of</strong> crime and violence suggest interestingcontradictions, such as <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> poorest members <strong>of</strong>society are rarely <strong>the</strong> perpetrators <strong>of</strong> violence; ra<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>perpetrators are frequently individuals and groups who haveenjoyed some prior upward social mobility or economicimprovement and <strong>the</strong>n find <strong>the</strong>mselves blocked from fur<strong>the</strong>rimprovement. These individuals and groups <strong>of</strong>ten express<strong>the</strong>ir frustrations through violence. This phenomenon wasobserved in <strong>the</strong> location <strong>of</strong> riots during <strong>the</strong> 1960s in <strong>the</strong> US,where violence occurred in those cities with <strong>the</strong> mostsuccessful anti-poverty programmes (i.e. Chicago, Detroitand Los Angeles). 33 It also reflects experience in Mumbaiand o<strong>the</strong>r cities, where recent poor rural–urban migrantswho are entering <strong>the</strong> labour force are rarely involved inviolence. 34While <strong>the</strong>se <strong>the</strong>ories and cases <strong>of</strong>fer complementaryand related evidence about <strong>the</strong> understanding <strong>of</strong> crime andviolence, <strong>the</strong>y are a backdrop to <strong>the</strong> daily lived experience <strong>of</strong>residents <strong>of</strong> Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Mexico City,Johannesburg or Manila, to name a few <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> many cities indeveloping countries where growing crime and violence areperceived as a major problem affecting all strata <strong>of</strong> society.During <strong>the</strong> late 1990s, <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> Mexicobegan to publicly discuss urban crime as a problem withmacro-economic consequences. This was an interestingdevelopment because, in relative terms, Mexico had acomparatively low level <strong>of</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> GDP due to violence, at 1.3per cent in 1997, compared to o<strong>the</strong>r Latin Americancountries such as Colombia and El Salvador, which both lostan estimated 25 per cent. 35 In contrast, <strong>the</strong> US, with a muchlarger GDP, had estimates <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> costs <strong>of</strong> violence reaching3.3 per cent <strong>of</strong> GDP. 36 This staggering amount has manyinteresting components, such as <strong>the</strong> estimated cost <strong>of</strong> ahomicide in <strong>the</strong> US valued at US$2 million, while estimateswere US$15,319 in South Africa and US$602,000 inAustralia, respectively, reflecting foregone income. 37Analytically, <strong>the</strong> WHO has distinguished between direct andindirect costs <strong>of</strong> violence in its review <strong>of</strong> 119 studies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>economic dimensions <strong>of</strong> interpersonal violence. Figure 1.3presents <strong>the</strong>se different costs. 38 The financing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se costsis a considerable weight on poor economies. Studies <strong>of</strong>Jamaica found that 90 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> costs <strong>of</strong> treatingvictims <strong>of</strong> violence at <strong>the</strong> Kingston Public Hospital were paidby <strong>the</strong> government. 39In this regard, it is interesting to observe differencesbetween cities within countries, such as <strong>the</strong> reductions incrime and violence achieved in Medellin, Colombia, where astrong mayor and civil society were determined to overcomedrug violence and dominance <strong>of</strong> ‘drug lords’, 40 compared tocontinued problems in Cali, where <strong>the</strong> drug cartels continueto exercise effective power. A third Colombian city, Bogotá,<strong>the</strong> national capital, has dramatically reduced crime andviolence. 41 And yet, although Colombia is globally perceivedas a violent country, more people died in armed violence in<strong>the</strong> favelas <strong>of</strong> Rio de Janeiro (49,913) from 1978 to 2000than in all <strong>of</strong> Colombia (39,000). 42In Brazil, more than 100 people are killed by gunsevery day, and <strong>the</strong> gun-related death rate in Rio de Janeiro ismore than double <strong>the</strong> national average. 43 Organized crimedemonstrated its great power in São Paulo during May andJune 2006 with its well-orchestrated attacks on police,followed by bloody retribution by <strong>the</strong> police. Press reportson São Paulo following this episode noted some startling data(see Box 1.2). Chapter 3 presents <strong>the</strong> drug dimensions <strong>of</strong>Interpersonal violence– Child abuse and neglect– Intimate partner violence– Elder abuse– Sexual violence– Workplace violence– Youth violence– O<strong>the</strong>r violent crimeThe emergence <strong>of</strong>ethnic identity as<strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> ethnicconflict andnationalistaspirations in <strong>the</strong>post-Cold War yearshas been widelynotedFigure 1.3Costs and benefits <strong>of</strong>interpersonal violenceSource: WHO, 2004, p6Direct costs and benefits– Costs <strong>of</strong> legal services– Direct medical costs– Direct perpetrator control costs– Costs <strong>of</strong> policing– Costs <strong>of</strong> incarceration– Costs <strong>of</strong> foster care– Private security contracts– Economic benefits to perpetratorsIndirect costs and benefits– Lost earnings and lost time– Lost investments in human capital– Indirect protection costs– Life insurance costs– Benefits to law enforcement– Productivity– Domestic investment– External investment and tourism– Psychological costs– O<strong>the</strong>r non-monetary costs