Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

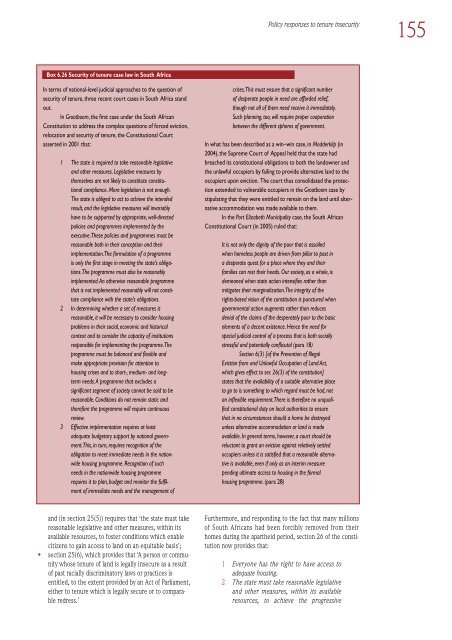

Policy responses to tenure insecurity155Box 6.26 Security <strong>of</strong> tenure case law in South AfricaIn terms <strong>of</strong> national-level judicial approaches to <strong>the</strong> question <strong>of</strong>security <strong>of</strong> tenure, three recent court cases in South Africa standout.In Grootboom, <strong>the</strong> first case under <strong>the</strong> South AfricanConstitution to address <strong>the</strong> complex questions <strong>of</strong> forced eviction,relocation and security <strong>of</strong> tenure, <strong>the</strong> Constitutional Courtasserted in 2001 that:1 The state is required to take reasonable legislativeand o<strong>the</strong>r measures. Legislative measures by<strong>the</strong>mselves are not likely to constitute constitutionalcompliance. Mere legislation is not enough.The state is obliged to act to achieve <strong>the</strong> intendedresult, and <strong>the</strong> legislative measures will invariablyhave to be supported by appropriate, well-directedpolicies and programmes implemented by <strong>the</strong>executive.These policies and programmes must bereasonable both in <strong>the</strong>ir conception and <strong>the</strong>irimplementation.The formulation <strong>of</strong> a programmeis only <strong>the</strong> first stage in meeting <strong>the</strong> state’s obligations.Theprogramme must also be reasonablyimplemented.An o<strong>the</strong>rwise reasonable programmethat is not implemented reasonably will not constitutecompliance with <strong>the</strong> state’s obligations.2 In determining whe<strong>the</strong>r a set <strong>of</strong> measures isreasonable, it will be necessary to consider housingproblems in <strong>the</strong>ir social, economic and historicalcontext and to consider <strong>the</strong> capacity <strong>of</strong> institutionsresponsible for implementing <strong>the</strong> programme.Theprogramme must be balanced and flexible andmake appropriate provision for attention tohousing crises and to short-, medium- and longtermneeds.A programme that excludes asignificant segment <strong>of</strong> society cannot be said to bereasonable. Conditions do not remain static and<strong>the</strong>refore <strong>the</strong> programme will require continuousreview.3 Effective implementation requires at leastadequate budgetary support by national government.This,in turn, requires recognition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>obligation to meet immediate needs in <strong>the</strong> nationwidehousing programme. Recognition <strong>of</strong> suchneeds in <strong>the</strong> nationwide housing programmerequires it to plan, budget and monitor <strong>the</strong> fulfilment<strong>of</strong> immediate needs and <strong>the</strong> management <strong>of</strong>crises.This must ensure that a significant number<strong>of</strong> desperate people in need are afforded relief,though not all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m need receive it immediately.Such planning, too, will require proper cooperationbetween <strong>the</strong> different spheres <strong>of</strong> government.In what has been described as a win–win case, in Modderklip (in2004), <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal held that <strong>the</strong> state hadbreached its constitutional obligations to both <strong>the</strong> landowner and<strong>the</strong> unlawful occupiers by failing to provide alternative land to <strong>the</strong>occupiers upon eviction. The court thus consolidated <strong>the</strong> protectionextended to vulnerable occupiers in <strong>the</strong> Grootboom case bystipulating that <strong>the</strong>y were entitled to remain on <strong>the</strong> land until alternativeaccommodation was made available to <strong>the</strong>m.In <strong>the</strong> Port Elizabeth Municipality case, <strong>the</strong> South AfricanConstitutional Court (in 2005) ruled that:It is not only <strong>the</strong> dignity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor that is assailedwhen homeless people are driven from pillar to post ina desperate quest for a place where <strong>the</strong>y and <strong>the</strong>irfamilies can rest <strong>the</strong>ir heads. Our society, as a whole, isdemeaned when state action intensifies ra<strong>the</strong>r thanmitigates <strong>the</strong>ir marginalization.The integrity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>rights-based vision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> constitution is punctured whengovernmental action augments ra<strong>the</strong>r than reducesdenial <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> claims <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> desperately poor to <strong>the</strong> basicelements <strong>of</strong> a decent existence. Hence <strong>the</strong> need forspecial judicial control <strong>of</strong> a process that is both sociallystressful and potentially conflicutal (para 18)Section 6(3) [<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prevention <strong>of</strong> IllegalEviction from and Unlawful Occupation <strong>of</strong> Land Act,which gives effect to sec 26(3) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> constitution]states that <strong>the</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> a suitable alternative placeto go to is something to which regard must be had, notan inflexible requirement.There is <strong>the</strong>refore no unqualifiedconstitutional duty on local authorities to ensurethat in no circumstances should a home be destroyedunless alternative accommodation or land is madeavailable. In general terms, however, a court should bereluctant to grant an eviction against relatively settledoccupiers unless it is satisfied that a reasonable alternativeis available, even if only as an interim measurepending ultimate access to housing in <strong>the</strong> formalhousing programme. (para 28)and (in section 25(5)) requires that ‘<strong>the</strong> state must takereasonable legislative and o<strong>the</strong>r measures, within itsavailable resources, to foster conditions which enablecitizens to gain access to land on an equitable basis’;• section 25(6), which provides that ‘A person or communitywhose tenure <strong>of</strong> land is legally insecure as a result<strong>of</strong> past racially discriminatory laws or practices isentitled, to <strong>the</strong> extent provided by an Act <strong>of</strong> Parliament,ei<strong>the</strong>r to tenure which is legally secure or to comparableredress.’Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, and responding to <strong>the</strong> fact that many millions<strong>of</strong> South Africans had been forcibly removed from <strong>the</strong>irhomes during <strong>the</strong> apar<strong>the</strong>id period, section 26 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> constitutionnow provides that:1 Everyone has <strong>the</strong> right to have access toadequate housing.2 The state must take reasonable legislativeand o<strong>the</strong>r measures, within its availableresources, to achieve <strong>the</strong> progressive