CORRUPTION Syndromes of Corruption

CORRUPTION Syndromes of Corruption

CORRUPTION Syndromes of Corruption

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Participation, institutions, and syndromes <strong>of</strong> corruption 59<br />

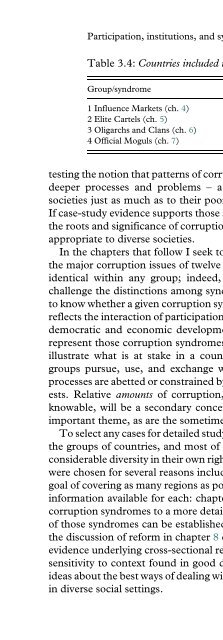

Table 3.4: Countries included in case-study chapters<br />

Group/syndrome<br />

Cases<br />

1 Influence Markets (ch. 4) USA, Japan, Germany<br />

2 Elite Cartels (ch. 5) Italy, Korea, Botswana<br />

3 Oligarchs and Clans (ch. 6) Russia, Mexico, Philippines<br />

4 Official Moguls (ch. 7) China, Kenya, Indonesia<br />

testing the notion that patterns <strong>of</strong> corruption vary in ways symptomatic <strong>of</strong><br />

deeper processes and problems – a notion that applies to advanced<br />

societies just as much as to their poorer and less democratic neighbors.<br />

If case-study evidence supports those arguments we can then understand<br />

the roots and significance <strong>of</strong> corruption – and propose reforms – in terms<br />

appropriate to diverse societies.<br />

In the chapters that follow I seek to identify, explore, and account for<br />

the major corruption issues <strong>of</strong> twelve countries. These issues will not be<br />

identical within any group; indeed, some are included because they<br />

challenge the distinctions among syndromes in useful ways. The goal is<br />

to know whether a given corruption syndrome exists, how it works, how it<br />

reflects the interaction <strong>of</strong> participation and institutions, and how it affects<br />

democratic and economic development. The four groups <strong>of</strong> countries<br />

represent those corruption syndromes rather than ‘‘system types.’’ They<br />

illustrate what is at stake in a country’s corruption, how people and<br />

groups pursue, use, and exchange wealth and power, and how those<br />

processes are abetted or constrained by institutions and contending interests.<br />

Relative amounts <strong>of</strong> corruption, to the extent that they are even<br />

knowable, will be a secondary concern; longer-term effects are a more<br />

important theme, as are the sometimes perverse effects <strong>of</strong> reforms.<br />

To select any cases for detailed study is <strong>of</strong> necessity to limit the analysis:<br />

the groups <strong>of</strong> countries, and most <strong>of</strong> the societies within them, embody<br />

considerable diversity in their own right. Those selected from each cluster<br />

were chosen for several reasons including their inherent importance, the<br />

goal <strong>of</strong> covering as many regions as possible, and the extent <strong>of</strong> case-study<br />

information available for each: chapters 4–7 put the idea <strong>of</strong> contrasting<br />

corruption syndromes to a more detailed test. If the existence and nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> those syndromes can be established with reasonable confidence, then<br />

the discussion <strong>of</strong> reform in chapter 8 can draw upon both the breadth <strong>of</strong><br />

evidence underlying cross-sectional research, and the depth <strong>of</strong> detail and<br />

sensitivity to context found in good descriptive case studies, to develop<br />

ideas about the best ways <strong>of</strong> dealing with contrasting corruption problems<br />

in diverse social settings.