You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Nicholas Riegel<br />

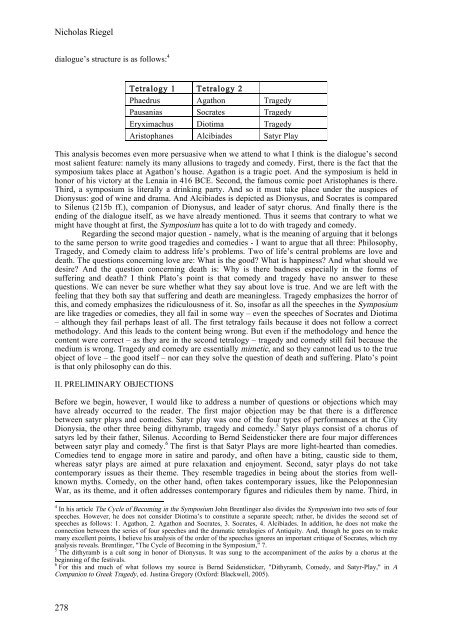

dialogue’s structure is as follows: 4<br />

278<br />

Tetralogy 1 Tetralogy 2<br />

Phaedrus Agathon Tragedy<br />

Pausanias Socrates Tragedy<br />

Eryximachus Diotima Tragedy<br />

Aristophanes Alcibiades Satyr Play<br />

This analysis becomes even more persuasive when we attend to what I think is the dialogue’s second<br />

most salient feature: namely its many allusions to tragedy and comedy. First, there is the fact that the<br />

symposium takes place at Agathon’s house. Agathon is a tragic poet. And the symposium is held in<br />

honor of his victory at the Lenaia in 416 BCE. Second, the famous comic poet Aristophanes is there.<br />

Third, a symposium is literally a drinking party. And so it must take place under the auspices of<br />

Dionysus: god of wine and drama. And Alcibiades is depicted as Dionysus, and Socrates is compared<br />

to Silenus (215b ff.), companion of Dionysus, and leader of satyr chorus. And finally there is the<br />

ending of the dialogue itself, as we have already mentioned. Thus it seems that contrary to what we<br />

might have thought at first, the <strong>Symposium</strong> has quite a lot to do with tragedy and comedy.<br />

Regarding the second major question - namely, what is the meaning of arguing that it belongs<br />

to the same person to write good tragedies and comedies - I want to argue that all three: Philosophy,<br />

Tragedy, and Comedy claim to address life’s problems. Two of life’s central problems are love and<br />

death. The questions concerning love are: What is the good? What is happiness? And what should we<br />

desire? And the question concerning death is: Why is there badness especially in the forms of<br />

suffering and death? I think Plato’s point is that comedy and tragedy have no answer to these<br />

questions. We can never be sure whether what they say about love is true. And we are left with the<br />

feeling that they both say that suffering and death are meaningless. Tragedy emphasizes the horror of<br />

this, and comedy emphasizes the ridiculousness of it. So, insofar as all the speeches in the <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

are like tragedies or comedies, they all fail in some way – even the speeches of Socrates and Diotima<br />

– although they fail perhaps least of all. The first tetralogy fails because it does not follow a correct<br />

methodology. And this leads to the content being wrong. But even if the methodology and hence the<br />

content were correct – as they are in the second tetralogy – tragedy and comedy still fail because the<br />

medium is wrong. Tragedy and comedy are essentially mimetic, and so they cannot lead us to the true<br />

object of love – the good itself – nor can they solve the question of death and suffering. Plato’s point<br />

is that only philosophy can do this.<br />

II. PRELIMINARY OBJECTIONS<br />

Before we begin, however, I would like to address a number of questions or objections which may<br />

have already occurred to the reader. The first major objection may be that there is a difference<br />

between satyr plays and comedies. Satyr play was one of the four types of performances at the City<br />

Dionysia, the other three being dithyramb, tragedy and comedy. 5 Satyr plays consist of a chorus of<br />

satyrs led by their father, Silenus. According to Bernd Seidensticker there are four major differences<br />

between satyr play and comedy. 6 The first is that Satyr Plays are more light-hearted than comedies.<br />

Comedies tend to engage more in satire and parody, and often have a biting, caustic side to them,<br />

whereas satyr plays are aimed at pure relaxation and enjoyment. Second, satyr plays do not take<br />

contemporary issues as their theme. They resemble tragedies in being about the stories from wellknown<br />

myths. Comedy, on the other hand, often takes contemporary issues, like the Peloponnesian<br />

War, as its theme, and it often addresses contemporary figures and ridicules them by name. Third, in<br />

4<br />

In his article The Cycle of Becoming in the <strong>Symposium</strong> John Brentlinger also divides the <strong>Symposium</strong> into two sets of four<br />

speeches. However, he does not consider Diotima’s to constitute a separate speech; rather, he divides the second set of<br />

speeches as follows: 1. Agathon, 2. Agathon and Socrates, 3. Socrates, 4. Alcibiades. In addition, he does not make the<br />

connection between the series of four speeches and the dramatic tetralogies of Antiquity. And, though he goes on to make<br />

many excellent points, I believe his analysis of the order of the speeches ignores an important critique of Socrates, which my<br />

analysis reveals. Brentlinger, "The Cycle of Becoming in the <strong>Symposium</strong>," 7.<br />

5<br />

The dithyramb is a cult song in honor of Dionysus. It was sung to the accompaniment of the aulos by a chorus at the<br />

beginning of the festivals.<br />

6<br />

For this and much of what follows my source is Bernd Seidensticker, "Dithyramb, Comedy, and Satyr-Play," in A<br />

Companion to Greek Tragedy, ed. Justina Gregory (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005).