- Page 1:

THE INTERNATIONAL PLATO SOCIETY UNI

- Page 5 and 6:

MONDAY, 15 TH JULY, 2013 3 Eros and

- Page 7:

Monday 15 th July, 2013

- Page 11 and 12:

Eros and Life-Values in Plato's Sym

- Page 13 and 14:

Stephen Halliwell proposition that

- Page 15 and 16:

Stephen Halliwell principle of a un

- Page 17:

The Ethics of Eros: Eudaimonism and

- Page 20 and 21:

Yuji Kurihara final clause that sho

- Page 22 and 23:

Yuji Kurihara wonderfully beautiful

- Page 24 and 25:

ABSTRACT Il ruolo e l'importanza de

- Page 26 and 27: Carolina Araujo if everything is en

- Page 28 and 29: Carolina Araujo changing objects du

- Page 30 and 31: Carolina Araujo Reeve, C. D. C. A s

- Page 32 and 33: David T. Runia transported to the i

- Page 34 and 35: David T. Runia given for why Plato

- Page 37: Method, Knowledge and Identity Chai

- Page 40 and 41: Lesley Brown ἀδελφοῦ ἢ

- Page 42 and 43: Lesley Brown “reconnaître”,

- Page 44 and 45: ABSTRACT The Kind of Knowledge Virt

- Page 46 and 47: Annie Larrivée the Alcibiades, amo

- Page 48 and 49: Annie Larrivée sense that he will

- Page 50 and 51: Annie Larrivée toward a (irrecover

- Page 52 and 53: Annie Larrivée bonheur comme étan

- Page 54 and 55: Annie Larrivée Avant de clore mon

- Page 56 and 57: Annie Larrivée PLATO [1997] The Sy

- Page 58 and 59: Alexis Pinchard dépasser la mesure

- Page 60 and 61: Alexis Pinchard exemple de nature m

- Page 62 and 63: Alexis Pinchard intelligence capabl

- Page 64 and 65: Alexis Pinchard vivant enfante enco

- Page 66 and 67: Alexis Pinchard foncière ; et, tom

- Page 68 and 69: Alexis Pinchard de sa parole vive,

- Page 70 and 71: Alexis Pinchard Donc, quand les mor

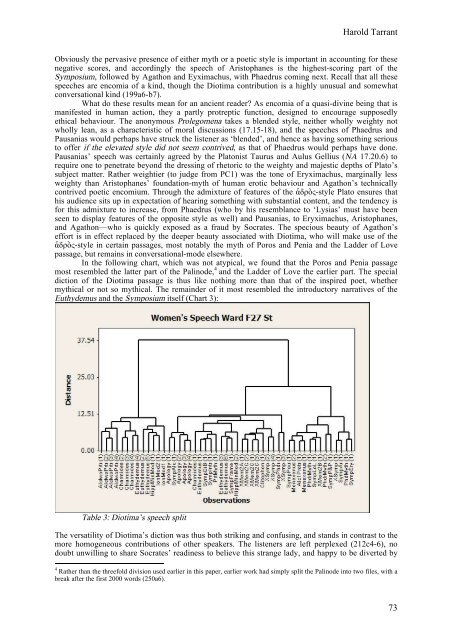

- Page 73 and 74: Stylistic Difference in the Speeche

- Page 75: Harold Tarrant contemplate the poss

- Page 79 and 80: Lettori antichi di Platone: il caso

- Page 81 and 82: Margherita Erbì o parti della trad

- Page 83 and 84: Margherita Erbì se non assoluto in

- Page 85 and 86: Ruby Blondell - Sandra Boehringer b

- Page 87 and 88: Ruby Blondell - Sandra Boehringer I

- Page 89 and 90: Ruby Blondell - Sandra Boehringer L

- Page 91 and 92: Ruby Blondell - Sandra Boehringer i

- Page 93 and 94: Gerard Boter being”, which unites

- Page 95 and 96: 4. εἴπερ τῳ ἄλλῳ ἀ

- Page 97: Plenary session Chair: Mary Margare

- Page 100 and 101: Mario Vegetti Fin qui, secondo Diot

- Page 102 and 103: Mario Vegetti oltreterrena delle id

- Page 104 and 105: Mario Vegetti è di peso (onchos) m

- Page 106 and 107: Mario Vegetti gnoseologica (oltre c

- Page 108 and 109: Mario Vegetti NUCCI (2009): M. NUCC

- Page 111: Plenary session Chair: Giuseppe Cam

- Page 115: The Frame Dialogue: Voices and Them

- Page 118 and 119: Narrazioni e narratori nel Simposio

- Page 120 and 121: Lidia Palumbo l’ascoltatore. Gius

- Page 122 and 123: Lidia Palumbo marcatamente che allo

- Page 124 and 125: Matthew D. Walker happiness in, or

- Page 126 and 127:

Matthew D. Walker has brought him j

- Page 128 and 129:

Matthew D. Walker from fully identi

- Page 130 and 131:

Dino De Sanctis vista la sua straor

- Page 132 and 133:

Dino De Sanctis A differenza di Eup

- Page 134 and 135:

No Invitation Required? A Theme in

- Page 136 and 137:

Giovanni R.F. Ferrari those around

- Page 138 and 139:

Diotima and kuèsis in the Light of

- Page 140 and 141:

Anne Gabriel Wersinger This traditi

- Page 142 and 143:

Anne Gabriel Wersinger 138 “Orphe

- Page 144 and 145:

Anne Gabriel Wersinger Bibl. BERNAB

- Page 147 and 148:

Phaedrus and the sophistic competit

- Page 149 and 150:

Hippias. 13 Noburu Notomi Since Hip

- Page 151 and 152:

speakers represents sophistic antag

- Page 153 and 154:

Eros sans expédient : Banquet, 179

- Page 155 and 156:

Annie Hourcade Sciou L’un des int

- Page 157 and 158:

Eros protrepōn: philosophy and sed

- Page 159 and 160:

Monopoly on seduction Olga Alieva A

- Page 161 and 162:

Olga Alieva of Chiron’s students

- Page 163 and 164:

Olga Alieva “worldly” passion i

- Page 165 and 166:

La natura intermedia di Eros: Pausa

- Page 167 and 168:

Lucia Palpacelli costretto a duplic

- Page 169 and 170:

Lucia Palpacelli la natura duplice

- Page 171 and 172:

Lucia Palpacelli sembra procedere,

- Page 173 and 174:

Philotimia and Philosophia in Plato

- Page 175 and 176:

Jens Kristian Larsen philotimia, wh

- Page 177 and 178:

Jens Kristian Larsen by philotimia,

- Page 179 and 180:

Olivier Renaut suivre dans le domai

- Page 181 and 182:

Olivier Renaut La philosophia et pl

- Page 183 and 184:

Olivier Renaut Il s’agit ni plus

- Page 185:

Eryximachus Chair: David T. Runia

- Page 188 and 189:

Hua-kuei Ho are noteworthy here. Fi

- Page 190 and 191:

Hua-kuei Ho emotions, perceptions a

- Page 192 and 193:

La medicina di Erissimaco: appunti

- Page 194 and 195:

Silvio Marino nemiche tra di loro.

- Page 196 and 197:

Silvio Marino dei fenomeni fisici;

- Page 198 and 199:

The concept of harmony (187 a-e) an

- Page 200 and 201:

Laura Candiotto and wine to prevent

- Page 202 and 203:

Laura Candiotto 26b1-3 Socrates app

- Page 204 and 205:

Laura Candiotto 2009, pp. 275-308.

- Page 206 and 207:

Richard Stalley an appeal to what h

- Page 208 and 209:

Richard Stalley enough: the city mu

- Page 211:

The Realm of the Metaxy Chair: Beat

- Page 214 and 215:

Michel Fattal Dans la seconde parti

- Page 216 and 217:

Michel Fattal est relation. L’amo

- Page 218 and 219:

Michel Fattal Moyen terme dynamique

- Page 220 and 221:

Michel Fattal désirent devenir sav

- Page 222 and 223:

Michel Fattal de la vie, mon cher S

- Page 224 and 225:

Perché tanta morte in un dialogo s

- Page 226 and 227:

Arianna Fermani I due poli “morte

- Page 228 and 229:

Arianna Fermani 2) rappresenta la c

- Page 230 and 231:

La nozione di intermedio nel Sympos

- Page 232 and 233:

Cristina Rossitto 228 Esiste una so

- Page 234 and 235:

Cristina Rossitto perché non è n

- Page 236 and 237:

Cristina Rossitto 232 dèmone, caro

- Page 238 and 239:

Reproduction, Immortality, and the

- Page 240 and 241:

Thomas M. Tuozzo applies more widel

- Page 242 and 243:

Thomas M. Tuozzo Syposium." Dialogu

- Page 244 and 245:

Piera De Piano loro intelligenza: i

- Page 246 and 247:

Piera De Piano animali. Esistono tr

- Page 248 and 249:

Piera De Piano l’immagine più pe

- Page 250 and 251:

ABSTRACT Socrates as a divine inter

- Page 253 and 254:

Why Agathon’s Beauty Matters Fran

- Page 255 and 256:

Francisco J. Gonzalez 5) In defendi

- Page 257 and 258:

Francisco J. Gonzalez the play with

- Page 259 and 260:

Francisco J. Gonzalez the power of

- Page 261 and 262:

Francisco J. Gonzalez next to him (

- Page 263 and 264:

Mario Regali rappresentate nel 411,

- Page 265 and 266:

Mario Regali Socrate giunge a mostr

- Page 267 and 268:

I. Einleitung Die Poetik des Philos

- Page 269 and 270:

2. Agathons Rede Irmgard Männlein-

- Page 271 and 272:

Irmgard Männlein-Robert ‚Poetik

- Page 273 and 274:

Aikaterini Lefka was just a new-bor

- Page 275 and 276:

Aikaterini Lefka Agathon 26 follows

- Page 277 and 278:

Aikaterini Lefka F. Graf, « Apollo

- Page 279 and 280:

Aikaterini Lefka O. Thomson, «Socr

- Page 281 and 282:

I. INTRODUCTION Tragedy and Comedy

- Page 283 and 284:

Nicholas Riegel contrast to both tr

- Page 285 and 286:

Nicholas Riegel even of the second

- Page 287:

Literary Form and Thought in Aristo

- Page 290 and 291:

Premessa Tra Henologia ed Agatholog

- Page 292 and 293:

Claudia Luchetti non concesso che i

- Page 294 and 295:

Claudia Luchetti e3, le parole dell

- Page 296 and 297:

Claudia Luchetti somiglianza che de

- Page 298 and 299:

Premise Between Henology and Agatho

- Page 300 and 301:

Claudia Luchetti If we analyze the

- Page 302 and 303:

Claudia Luchetti (211b1, e4), prese

- Page 304 and 305:

Claudia Luchetti to establish a jus

- Page 306 and 307:

Claudia Luchetti Philosophie. Inter

- Page 308 and 309:

Aristofane e l’ombra di Protagora

- Page 310 and 311:

Michele Corradi quella del grande d

- Page 312 and 313:

Michele Corradi Platone vuol celare

- Page 314 and 315:

Samuel Scolnicov by more noise and

- Page 316 and 317:

Samuel Scolnicov Hoffman, Ernst 194

- Page 318 and 319:

Roslyn Weiss two conjoined wholes a

- Page 320 and 321:

Roslyn Weiss prohibition, and he an

- Page 323:

Plenary session Chair: Verity Harte

- Page 326 and 327:

Thomas Alexander Slezák weil er es

- Page 328 and 329:

Thomas Alexander Slezák (507e6 - 5

- Page 330 and 331:

ABSTRACT Chi è il Socrate del Simp

- Page 333:

Diotima and the Ocean of Beauty Cha

- Page 336 and 337:

Francisco L. Lisi especial, con la

- Page 338 and 339:

Francisco L. Lisi y Bueno. El diál

- Page 340 and 341:

L'océan du beau : les Formes plato

- Page 342 and 343:

Arnaud Macé caractérisation de ce

- Page 344 and 345:

Arnaud Macé Timée (47b5-c4) on ex

- Page 346 and 347:

Arnaud Macé à cette évaluation c

- Page 348 and 349:

ABSTRACT Socrates’ Thea: The Desc

- Page 351:

Eros, Poiesis and Philosophical Wri

- Page 354 and 355:

Philip Krinks III: PAUSANIAS AND PR

- Page 356 and 357:

Philip Krinks the nature, including

- Page 358 and 359:

Philip Krinks methodological focus,

- Page 360 and 361:

Gabriel Danzig forth. The only part

- Page 362 and 363:

Gabriel Danzig was a special target

- Page 364 and 365:

Gabriel Danzig way. While there may

- Page 366 and 367:

Gabriel Danzig not only shows Agath

- Page 368 and 369:

Gabriel Danzig describes the origin

- Page 370 and 371:

Giovanni Casertano sia φιλόσο

- Page 372 and 373:

Giovanni Casertano altre specie di

- Page 374 and 375:

Giovanni Casertano umano nella sua

- Page 377:

The Picture of Socrates Chair: Chri

- Page 380 and 381:

Edward C. Halper eternal (cf. 29d-3

- Page 382 and 383:

Edward C. Halper understands that t

- Page 384 and 385:

Edward C. Halper would be undermine

- Page 386 and 387:

ABSTRACT Platon als Lehrer des Sokr

- Page 388 and 389:

Graciela E. Marcos de Pinotti Sócr

- Page 390 and 391:

Graciela E. Marcos de Pinotti sabid

- Page 392 and 393:

Graciela E. Marcos de Pinotti (1969

- Page 394 and 395:

Federico M. Petrucci di scena dell'

- Page 396 and 397:

Federico M. Petrucci dell'oplita e

- Page 399:

ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Dipartimento d