- Page 1 and 2:

© Dr. Andreas J. Werner Library Bu

- Page 3 and 4:

the academic environment operates b

- Page 5 and 6:

Argentine Estudio Borrachia - PYRE

- Page 7 and 8:

6◦ see: Six Degrees Australia All

- Page 9 and 10:

The redevelopment of the Library ai

- Page 11 and 12:

Mona Vale Civic Centre, Sydney-Mona

- Page 13 and 14:

Brown Falconer Group, Maylands, SA

- Page 15 and 16:

create a new model, and to create a

- Page 17 and 18:

much reduced scale. You can wander

- Page 19 and 20:

Fulton Trotter, Brisbane, QLD - Aus

- Page 21 and 22:

as planning set-off points. Walls h

- Page 23 and 24:

Haskell Architects, Melbourne, VIC

- Page 25 and 26:

ECU Library is brought to life thro

- Page 27 and 28:

McBride Charles Ryan, Melbourne-Pra

- Page 29 and 30:

Six Degrees Pty Ltd Architects, Mel

- Page 31 and 32:

Terroir Architects, Sydney, NSW - A

- Page 33 and 34:

Council were instrumental in the in

- Page 35 and 36:

Collaborative Learning Centre, Univ

- Page 37 and 38:

ARTEC - Bettina Götz Richard Manah

- Page 39 and 40:

Architekten Croce-Klug, Graz - Aust

- Page 41 and 42:

egleitet von einer sorgfältigen Ü

- Page 43 and 44:

Die übergeordnete Steuerung wird d

- Page 45 and 46:

Heidl Architekten ZT GmbH, Linz - A

- Page 47 and 48:

Ensemble von SOWI-Fakultät, Wohn-,

- Page 49 and 50:

schossige Aufstockung der HTL und d

- Page 51 and 52:

Architektur und Nachhaltigkeit. „

- Page 53 and 54:

einem Bedarf. Denn Bildschirmarbeit

- Page 55 and 56:

Schiefer, ansonsten anthrazitfarben

- Page 57 and 58:

oder die Übernahme eines Stils gar

- Page 59 and 60:

Architektur Stögmüller, Linz - Au

- Page 61 and 62:

Geschäftsführer der BIG, Matthias

- Page 63 and 64:

Belgium ABSCIS Architecten, Gent -

- Page 65 and 66:

l’état d’avancement des bâtim

- Page 67 and 68:

La Biblioteca Pública de Puurs és

- Page 69 and 70:

Plantijn Hogeschool (Library), Antw

- Page 71 and 72:

Bulgaria Studio 8 ½, Plovdiv, Bulg

- Page 73 and 74:

Canada acdf Architecture, Montréal

- Page 75 and 76:

Atelier TAG (Manon Asselin), Montr

- Page 77 and 78:

Original features were retained whe

- Page 79 and 80:

for evolving library activities is

- Page 81 and 82:

Description of the winning project

- Page 83 and 84:

DAM Architects, Montréal, QC - Can

- Page 85 and 86:

Library and Learning Commons, Cente

- Page 87 and 88:

eading rooms at each floor bring 65

- Page 89 and 90:

"It sort of reminds me of a pile of

- Page 91 and 92:

Dan S. Hanganu, Montréal, QC - Can

- Page 93 and 94:

esidential dwellings and sophistica

- Page 95 and 96:

The resultant gently sloping buildi

- Page 97 and 98:

Kohn Shnier Architects, Toronto, ON

- Page 99 and 100:

Moffat Kinoshita, Hamilton, ON - Ca

- Page 101 and 102:

promote the use of wood and wood pr

- Page 103 and 104:

Central Erin Mills Multi-Use Comple

- Page 105 and 106:

Moriyama & Teshima Architects, Toro

- Page 107 and 108:

Bibliothèque Marc Favreau, Montré

- Page 109 and 110:

David Premi (dp.Ai), Hamilton, ON -

- Page 111 and 112:

interior stairs will be removed and

- Page 113 and 114:

polished aluminum reflects the Stra

- Page 115 and 116:

eplacement. Located on top of a hil

- Page 117 and 118:

The Library contains dedicated Teen

- Page 119 and 120:

Teeple Architects, Toronto, ON - Ca

- Page 121 and 122:

library in the winter months. The f

- Page 123 and 124:

Zeidler Partnership Architecten, To

- Page 125 and 126:

conceptualización y configuración

- Page 127 and 128:

GL Studio - Gong Lu Architectural D

- Page 129 and 130:

library takes form and connotation

- Page 131 and 132:

Columbia Felipe Uribe de Bedout Arc

- Page 133 and 134:

Though the 11,500-square-foot libra

- Page 135 and 136:

creando una nueva espacialidad enri

- Page 137 and 138:

Randić Turato Architektonski Biro

- Page 139 and 140:

storage, technology, supply and a p

- Page 141 and 142:

institutions. With its public funct

- Page 143 and 144:

http://www.bosch-fjord.com Librarie

- Page 145 and 146:

Fogh & Følner, Lyngby - Denmark ht

- Page 147 and 148:

With a capacity of 1600 students th

- Page 149 and 150:

C.F.Mǿller Architects, Aarhus - De

- Page 151 and 152:

Four large glass panels afford view

- Page 153 and 154:

spaces, exhibitions and events,”

- Page 155 and 156:

Estonia 3+1 architects, Tallinn - E

- Page 157 and 158:

Finland Anttinen Oiva Architects, H

- Page 159 and 160:

Heikkinen-Komonen, Helsinki - Finla

- Page 161 and 162:

Built in 1965, the Library needed a

- Page 163 and 164:

Library Hollola, Hollola - Finland

- Page 165 and 166:

The interior was designed to be spa

- Page 167 and 168:

Médiathèque François Mitterand,

- Page 169 and 170:

Nous avons opté pour un projet sim

- Page 171 and 172:

School of 100 students comprising a

- Page 173 and 174:

perceived from the entry hall, allo

- Page 175 and 176:

au service du public. Il favorise e

- Page 177 and 178:

Patrick Berger, Jacques Anziutti, P

- Page 179 and 180:

Mais au final, ces copeaux de récu

- Page 181 and 182:

Bibliothèque multimédia de Guére

- Page 183 and 184:

Maîtrise d’ouvrage Ville de Font

- Page 185 and 186:

Chabanne & Partenaires (Jean Chaban

- Page 187 and 188:

Olivier Chaslin, Paris - France htt

- Page 189 and 190:

Pierre Colboc, Paris - France http:

- Page 191 and 192:

cr&on, Grenoble - France Thierry Ra

- Page 193 and 194:

dda devaux & devaux architectes, Pa

- Page 195 and 196:

lecture et vis à vis de l’inform

- Page 197 and 198:

peinte de brun sombre, se présente

- Page 199 and 200:

Médiathèque, utilisé comme parvi

- Page 201 and 202:

Transformation de l´Hôtel Dieu en

- Page 203 and 204:

Bruno Gaudin Architecte D.P.L.G., P

- Page 205 and 206:

incluait la conservation de plusieu

- Page 207 and 208:

Christoph Gulizzi Architecte, Marse

- Page 209 and 210:

Bruno Huerre Architecte, Paris - Fr

- Page 211 and 212:

Jourda Architectes, Paris, Wien - F

- Page 213 and 214:

flowers. Anne Lacaton & Jean Philip

- Page 215 and 216:

équipée d’un auvent sérigraphi

- Page 217 and 218:

lieu, surtout quand elle fut vécue

- Page 219 and 220:

The whole being organised in layers

- Page 221 and 222:

which three finalists were chosen:

- Page 223 and 224:

École Nationale des Greffes a Dijo

- Page 225 and 226:

Bibliothèque Université Paris VII

- Page 227 and 228:

Atelier Antoinette Robain Claire Gu

- Page 229 and 230:

Serero, Yoichi Ozawa, Ran She, Fabr

- Page 231 and 232:

programme Construction d'une biblio

- Page 233 and 234:

circulaire, refermé par la façade

- Page 235 and 236:

Wilmotte et Associés SA d´archite

- Page 237 and 238:

Fenster gegen Glastürelemente einb

- Page 239 and 240:

Grundkonstruktion, nimmt die Lasten

- Page 241 and 242:

ausnimmt, liegt nicht zuletzt daran

- Page 243 and 244:

opportunity to contemplate and comm

- Page 245 and 246:

worden. Die in die Jahre gekommene

- Page 247 and 248:

sogar aus dem Haus hinaus aufs Dach

- Page 249 and 250:

durch Umbauten und Leerstand in Ver

- Page 251 and 252:

verbunden, um so mit einer öffentl

- Page 253 and 254:

BHPS Architekten, Gesellschaft von

- Page 255 and 256:

Preisträgern. Da das Juryprotokoll

- Page 257 and 258:

eading table, a striped and upholst

- Page 259 and 260:

der Fluß, der sich in der Abenddä

- Page 261 and 262:

Bauherr: TU Darmstadt € 74.000.00

- Page 263 and 264:

Prof. Ulrich Coersmeier GmbH, Köln

- Page 265 and 266:

ursprünglichen Gebäudes zu beeint

- Page 267 and 268:

gleichmäßigen Raster aus hochform

- Page 269 and 270:

„Casinohof“. Die Hoffassaden ob

- Page 271 and 272:

FAR Frohn & Rojas, Berlin - Santiag

- Page 273 and 274:

The buildings of the new campus run

- Page 275 and 276:

herein, dieser Bereich ist öffentl

- Page 277 and 278:

Gao Shusan, Dominika Gnatowicz, Sa

- Page 279 and 280:

energetische Ausrichtung des Hochsc

- Page 281 and 282:

efindet. Während der eingeschossig

- Page 283 and 284:

Innovatives Bildungs- und Bibliothe

- Page 285 and 286:

Fußboden. Der Bodenbelag der öffe

- Page 287 and 288:

Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig- Wi

- Page 289 and 290:

Auf den Baufeldern an der Duisburge

- Page 291 and 292:

Wiederaufbau der historischen Bibli

- Page 293 and 294:

4. Preis (6.000 Mark): Konermann Pa

- Page 295 and 296:

The former manufacturer’s mansion

- Page 297 and 298:

Aufenthaltsräume. Der Neubau umfas

- Page 299 and 300:

Federation of Library Associations

- Page 301 and 302:

Straßenbahndepot Sachsenhausen, Bi

- Page 303 and 304:

Die ersten Preisträger beschreiben

- Page 305 and 306:

Baukulturführer 20 Bibliotheks- un

- Page 307 and 308:

einzelne Fensterscheiben sind blau

- Page 309 and 310:

MSP Architekten, Dortmund - Germany

- Page 311 and 312:

entworfen hat. Lothar Jeromin erhie

- Page 313 and 314:

Laborflügeln ist eine Art „Mall

- Page 315 and 316:

Ausleiher können Bücher dort kün

- Page 317 and 318:

Forschungskomplexes ein und reagier

- Page 319 and 320:

lässt das Gebäude von der Frankfu

- Page 321 and 322:

Schrammel Architekten (Stefan Schra

- Page 323 and 324:

Das Collegium Hungaricum Berlin keh

- Page 325 and 326:

SKE Group Facility Management GmbH,

- Page 327 and 328:

Staatliches Bauamt I, Köln - Germa

- Page 329 and 330:

Storch Ehlers Partner Architekten,

- Page 331 and 332:

Museumsbuchhandlung sowie eine Caf

- Page 333 and 334:

Akzent. (Wilford) Ulrich Wolf & Hel

- Page 335 and 336:

Planungsgemeinschaft zauberscho(e)n

- Page 337 and 338:

Hong Kong Cheungvogl, Hong Kong - H

- Page 339 and 340:

Hungary Török és Balázs Épít

- Page 341 and 342:

Ireland A & D (Architecture & Desig

- Page 343 and 344:

Carr Cotter & Naessens, Cork - Irel

- Page 345 and 346:

serving all three. The new library

- Page 347 and 348:

plaza to the main circulation route

- Page 349 and 350:

The library is primarily a naturall

- Page 351 and 352:

Italy 2A+P/A Associates, Roma - Ita

- Page 353 and 354:

“living room of the city”, a me

- Page 355 and 356:

Die neue Bibliothek wird von zwei S

- Page 357 and 358:

Nuova Biblioteca Communale e Centro

- Page 359 and 360:

matter and lightness, solidity and

- Page 361 and 362:

orthogonal paths to the new Piazza

- Page 363 and 364:

use of perimeter "diaphragm" made w

- Page 365 and 366:

Finally, other studies contain cabi

- Page 367 and 368:

osco prolunga idealmente l’interv

- Page 369 and 370:

Japan Tadao Ando Architect & Associ

- Page 371 and 372:

warmer months. Calibrated and calcu

- Page 373 and 374:

Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects,

- Page 375 and 376:

phenomenon appears in the most anci

- Page 377 and 378:

Literature: Shinkenchiku 0911, GA J

- Page 379 and 380:

SANAA Architects (Kazuyo Sejima & R

- Page 381 and 382:

exterior design collaboration: SANA

- Page 383 and 384:

The branch library of the National

- Page 385 and 386:

In 2006, in the contest, held by th

- Page 387 and 388:

Mexico Legorreta + Legorreta, Mexic

- Page 389 and 390:

The best plan that gave the team of

- Page 391 and 392:

Netherlands 19Het Atalier architect

- Page 393 and 394:

includes." Information Landscape Wi

- Page 395 and 396:

is not only lyrically receive help,

- Page 397 and 398:

the new Central Public Library Perm

- Page 399 and 400:

andere functies, synergie. In dit g

- Page 401 and 402:

ecame part of the higher profession

- Page 403 and 404:

Corlaer 2 College, Nijkerk (Prov. G

- Page 405 and 406:

all important as a whole. They tran

- Page 407 and 408:

Arbeiten werden die jeweiligen Baut

- Page 409 and 410:

Campus 2020 is the accommodation pl

- Page 411 and 412:

FJ Stands & Interieurs B.V. Bussum

- Page 413 and 414:

qualities and spatial layout of the

- Page 415 and 416:

elements. The layout is easily inte

- Page 417 and 418:

Architectuurstudio HH (Herman Hertz

- Page 419 and 420:

different themes. Besides a large c

- Page 421 and 422:

In de U bevinden zich de werkplekke

- Page 423 and 424:

Bibliotheek en Appartementen, Beurs

- Page 425 and 426:

landscape. Each zone has been given

- Page 427 and 428:

provide natural and efficient cooli

- Page 429 and 430:

added value for the environment com

- Page 431 and 432:

Mediacenter - The Netherlands Insti

- Page 433 and 434:

Al Kuwari, Minister, Culture, Arts

- Page 435 and 436:

University. Through a mix of Medite

- Page 437 and 438:

uilding looks solid, according to t

- Page 439 and 440:

faculty in the infield located and

- Page 441 and 442:

auditorium by efficiently positioni

- Page 443 and 444:

new additions as well as various re

- Page 445 and 446:

door een van de atria naar de eerst

- Page 447 and 448:

Arthouse Architecture Ltd., Nelson

- Page 449 and 450:

seasonal temperature requirements.

- Page 451 and 452:

Paraparaumu Library, Paraparaumu -

- Page 453 and 454:

Norway a-lab Arkitekturlaboratoriet

- Page 455 and 456:

The project consists of two buildin

- Page 457 and 458:

hall has a window with curtains so

- Page 459 and 460:

college, helping to remove any barr

- Page 461 and 462:

University College Østfold, Halden

- Page 463 and 464:

Niels Torp Architects, Oslo - Norwa

- Page 465 and 466:

Peru Edificio Metropolis, Lima - Pe

- Page 467 and 468:

Stores closed, inaccessible to the

- Page 469 and 470:

Portugal Aires Mateus & Associados,

- Page 471 and 472:

Ricardo Carvalho + Joana Vilhena Ar

- Page 473 and 474:

Serôdio Furtado Arquitectos, Porto

- Page 475 and 476:

Singapore Look Architects Pte. Ltd.

- Page 477 and 478:

generations. The library collection

- Page 479 and 480:

Professional Team: Adam Essa Shabod

- Page 481 and 482:

Sitting on a patch of high ground,

- Page 483 and 484:

coffered wood panelled ceiling a st

- Page 485 and 486:

Este edificio se plantea con la vol

- Page 487 and 488:

adjacent medieval city gateway (the

- Page 489 and 490:

and corrupted it notably. The inter

- Page 491 and 492:

Contell - Martínez Architectos, Va

- Page 493 and 494:

dosmasuno arquitectos, Madrid - Spa

- Page 495 and 496:

Espinet Ubach Architectes, Barcelon

- Page 497 and 498:

iqualificazione e perno tra le dive

- Page 499 and 500:

San José Marques, Barcelona - Spai

- Page 501 and 502:

una plaza cubierta. "Refleja la ide

- Page 503 and 504:

The place usually helps us facing t

- Page 505 and 506:

Project description In 2005 Cañada

- Page 507 and 508:

The library building connects old w

- Page 509 and 510:

uscando las vistas hacia el jardín

- Page 511 and 512:

la cultura», afirmó. Bosch, que d

- Page 513 and 514:

uisánchez arquitectes, Barcelona -

- Page 515 and 516:

entorno, el acceso norte del vestí

- Page 517 and 518:

El ayuntamiento de Mollet del Vall

- Page 519 and 520:

Sweden FOJAB arkitekter, Lund - Swe

- Page 521 and 522:

Five years have passed since the po

- Page 523 and 524:

Switzerland ACAU - atelier coopéra

- Page 525 and 526:

he himself regarded Werner Oechslin

- Page 527 and 528:

The whole intervention is more of a

- Page 529 and 530:

short time to put on the ground flo

- Page 531 and 532:

“The building typology of our des

- Page 533 and 534:

Innenschale die den heutigen Anspr

- Page 535 and 536:

the level -1 allows optimal natural

- Page 537 and 538:

uilding contractors, property devel

- Page 539 and 540:

Turkey Akant Tasarim & Restorasyon

- Page 541 and 542:

United Kingdom 3Dreid, Birmingham -

- Page 543 and 544:

which are lifted or set within the

- Page 545 and 546:

Aldington Craig Collinge, Albury Th

- Page 547 and 548:

the public domain is enriched by st

- Page 549 and 550:

Phase Two of Birmingham City Univer

- Page 551 and 552:

Atkins Design Studio, Epsom, Surrey

- Page 553 and 554:

Stock is integrated in a single seq

- Page 555 and 556:

identified with different colours w

- Page 557 and 558:

strong analytical approach with sym

- Page 559 and 560:

The historay of the place seemed at

- Page 561 and 562:

Stoke 6 th Form College, Stoke-on-T

- Page 563 and 564:

Begründung des Preisgerichtes. Im

- Page 565 and 566:

The Soheil Abedian School of Archit

- Page 567 and 568:

Betty and Gordon Moore Library, Uni

- Page 569 and 570:

drdharchitects, London - UK http://

- Page 571 and 572:

Farrells (Terry Farrell), London, E

- Page 573 and 574:

for a number of commissioned artist

- Page 575 and 576:

John Spoor Broome Library, Californ

- Page 577 and 578:

activities for the students of the

- Page 579 and 580:

Kempe Centre, Wye College Imperial

- Page 581 and 582:

shelving space for books, a new wor

- Page 583 and 584:

Long & Kentish architects, London -

- Page 585 and 586:

John McAslan + Partners, Manchester

- Page 587 and 588:

authors and members of the general

- Page 589 and 590:

The building as a whole was complet

- Page 591 and 592:

Pringle Richards Sharrat Architects

- Page 593 and 594:

Reiach and Hall Architects, Edinbur

- Page 595 and 596:

concrete frame. The reception and r

- Page 597 and 598:

London Borough Enfield, Fore Street

- Page 599 and 600:

simulations revealed a potential pr

- Page 601 and 602:

Hall. Installation costs were share

- Page 603 and 604:

Dr Sarah Thomas, Bodley’s Librari

- Page 605 and 606:

Scott’s alterations inserted new

- Page 607 and 608:

The Women´s Library, London Metrop

- Page 609 and 610:

“The students love it. It's full

- Page 611 and 612:

isolation from the center, it seeme

- Page 613 and 614:

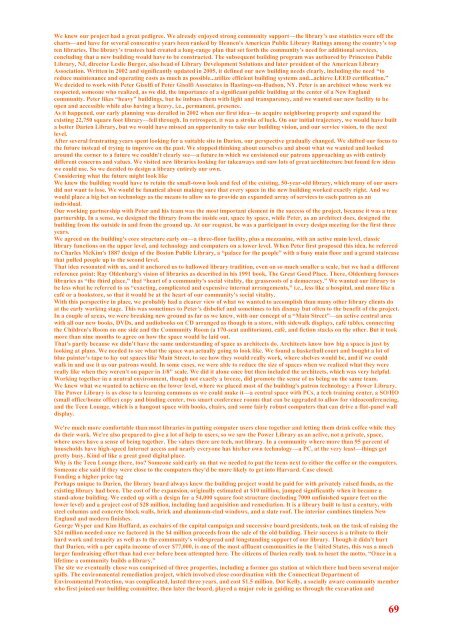

Project description The $108.7 mill

- Page 615 and 616:

Alspector Architecture, LLC - USA h

- Page 617 and 618:

ATA / Beilharz Architects, Cincinna

- Page 619 and 620:

The Town Board approved the library

- Page 621 and 622:

"Their (Ann Beha Architects') advic

- Page 623 and 624:

Gunnar Birkerts (& Association), We

- Page 625 and 626: 2006 Green Roof Award of Excellence

- Page 627 and 628: Agave Library, Phoenix, Arizona - U

- Page 629 and 630: draws air from the open floors belo

- Page 631 and 632: Mills Memorial Library, McMaster Un

- Page 633 and 634: Development and JMI Sports, and con

- Page 635 and 636: classrooms and a 65-seat screening

- Page 637 and 638: University of Colorado, Anschutz Me

- Page 639 and 640: exterior has added light, energy an

- Page 641 and 642: Scotland and England. Some of his m

- Page 643 and 644: We value collegiality and working t

- Page 645 and 646: [In the early 1900s, Andrew Carnegi

- Page 647 and 648: “From the start, our students mad

- Page 649 and 650: University of Las Vegas, Lied Libra

- Page 651 and 652: and lounge areas. The library and g

- Page 653 and 654: Eskind Library is a dynamic additio

- Page 655 and 656: (http://www.dewberry.com/Libraries/

- Page 657 and 658: collection. The library also includ

- Page 659 and 660: The design team worked with the Car

- Page 661 and 662: protects the books from harmful, co

- Page 663 and 664: under flanking low roofs that serve

- Page 665 and 666: As an integral part of Iowa City´s

- Page 667 and 668: townhouses (“36” and “38”)

- Page 669 and 670: FGM Frye Gillan Molinaro Architects

- Page 671 and 672: included upgrades for seismic, mech

- Page 673 and 674: The Tenley-Friendship Library has s

- Page 675: Gehry Partners, LLP, Los Angeles -

- Page 679 and 680: the City Commission for approval in

- Page 681 and 682: Libraries: Howard County Library, C

- Page 683 and 684: Santa Clara Central Park Library, S

- Page 685 and 686: uilding which is owned by The New Y

- Page 687 and 688: The architectural character of this

- Page 689 and 690: Hartman Cox, Washington - USA http:

- Page 691 and 692: approximately $55,000 per year in e

- Page 693 and 694: Montclair Public Library, Montclair

- Page 695 and 696: In 1948, an issue of Princeton Alum

- Page 697 and 698: to-date technology in this 134,200

- Page 699 and 700: Rita and Truett Smith Central Publi

- Page 701 and 702: (http://www.aallnet.org/main-menu/P

- Page 703 and 704: solutions to meet the challenges of

- Page 705 and 706: Philip Johnson (*08.07.1906 Clevela

- Page 707 and 708: (Johnston) South Park Library, Seat

- Page 709 and 710: storytelling corner, fanciful rCoun

- Page 711 and 712: foot facility in the Glickman Libra

- Page 713 and 714: separated from each other by a conv

- Page 715 and 716: ascending stair up to the floors of

- Page 717 and 718: VP Sam Overton. “The Estelle M. B

- Page 719 and 720: original. Architect designed furnit

- Page 721 and 722: Litman Architecture, Warren, RI - U

- Page 723 and 724: and new reference and circulation a

- Page 725 and 726: Suzzallo Library’s importance to

- Page 727 and 728:

Peabody reading room sits neatly wi

- Page 729 and 730:

space-saving alternative allows muc

- Page 731 and 732:

United States Senate Library, Renov

- Page 733 and 734:

Consisting of a 20,000 s.f. communi

- Page 735 and 736:

MSKTD & Associates, Inc., Fort Wayn

- Page 737 and 738:

Withworth University, Cheney Cowles

- Page 739 and 740:

“We took off the old copper dome

- Page 741 and 742:

Los Gatos Library, Los Gatos, CA -

- Page 743 and 744:

gather, with an open reading room a

- Page 745 and 746:

is most clearly expressed within th

- Page 747 and 748:

•Improve and update operational a

- Page 749 and 750:

Overland Partners Architects, San A

- Page 751 and 752:

architecture. The existing building

- Page 753 and 754:

GSM is the second largest building

- Page 755 and 756:

platform that ties the components t

- Page 757 and 758:

campus of Nanjing University. The n

- Page 759 and 760:

world-class research university, co

- Page 761 and 762:

Scope of Services: St. George’s S

- Page 763 and 764:

and charging stations. Traditional

- Page 765 and 766:

Lee Harris Pomeroy Architects, New

- Page 767 and 768:

Robert Hoag Rawlings Public Library

- Page 769 and 770:

Prozign Architects, Houston, TX - U

- Page 771 and 772:

Wedged between two courtyards, the

- Page 773 and 774:

addressed the client’s vision for

- Page 775 and 776:

The Kinlaw Library / Kirkland Learn

- Page 777 and 778:

Awards: Highly Commended, AR MIPIM

- Page 779 and 780:

The design team was handed a blank

- Page 781 and 782:

Library Media Center, Glendale Comm

- Page 783 and 784:

Rob Wellington Quigley, San Diego-P

- Page 785 and 786:

to flexibly accommodate day to day

- Page 787 and 788:

attained a pride of place status wi

- Page 789 and 790:

The Harvard-Radcliffe Hillel provid

- Page 791 and 792:

purpose that promotes Sacred Heart

- Page 793 and 794:

Schacht Aslani Architects, Seattle,

- Page 795 and 796:

Boston Athenaeum, Boston, MA - USA

- Page 797 and 798:

a vegetated roof. The facility offe

- Page 799 and 800:

The revitalized Fondren Library ful

- Page 801 and 802:

Queen´s University, McClay Library

- Page 803 and 804:

Branding graphics, bright interior

- Page 805 and 806:

opportunities for all students, inc

- Page 807 and 808:

SmithGroup, Detroit, MI - USA http:

- Page 809 and 810:

offices and classrooms. The buildin

- Page 811 and 812:

the last ten years, has long sought

- Page 813 and 814:

The Golden West College Learning Re

- Page 815 and 816:

and electrical systems have been co

- Page 817 and 818:

available stack space for the libra

- Page 819 and 820:

programmed areas for Children, Teen

- Page 821 and 822:

structure incorporated exposed prec

- Page 823 and 824:

Offices, Multi‐Media Classroom, C

- Page 825 and 826:

The original library was built in 1

- Page 827 and 828:

The facility will occupy a site nea

- Page 829 and 830:

Awards: AIA Portland Chapter Merit

- Page 831 and 832:

the current campus. Using innovativ

- Page 833 and 834:

monitors and LCD projection for med

- Page 835 and 836:

The exterior is clad in precast con

- Page 837 and 838:

Yard. An area of the second floor w

- Page 839 and 840:

Wendell Burnette Architects, Phoeni

- Page 841 and 842:

University design guidelines for th

- Page 843 and 844:

U.S. It is a secure temperature/hum

- Page 845 and 846:

(WRT) Saint Charley Seminary Ryan M

- Page 847 and 848:

Canberra (Australian Capital Territ

- Page 849 and 850:

Surry Hills (New South Wales) Surry

- Page 851 and 852:

Perg (Bundesland Oberösterreich) B

- Page 853 and 854:

Veurne (Arrondissm.Veurne, Prov. We

- Page 855 and 856:

(Prov. Ontario, County Frontenac) P

- Page 857 and 858:

Toronto (Prov. Ontario, Rég. Great

- Page 859 and 860:

Beijing Tsinghua Law Library compte

- Page 861 and 862:

Nuuts (Greenland) Katuag Cultur Cen

- Page 863 and 864:

Bourg lès Valence (Dép. Drôme, R

- Page 865 and 866:

Grand Moulins see: Paris Universit

- Page 867 and 868:

Nilvange (Thionville) (Dép. Mosell

- Page 869 and 870:

Saint-Gaudens (Dép. Haute-Garonne,

- Page 871 and 872:

Balingen (Bundesland Baden-Württem

- Page 873 and 874:

Dresden (Bundesland Sachsen) St. Be

- Page 875 and 876:

Hamburg (Bundesland Hamburg) Intern

- Page 877 and 878:

Mannheim (Bundesland Baden-Württem

- Page 879 and 880:

Stendal (Bundesland Sachsen-Anhalt)

- Page 881 and 882:

Lismore (Prov. Munster) Library Hea

- Page 883 and 884:

San Lorenzo di Sabato (Prov. Bolzan

- Page 885 and 886:

Šiauliai (County Šiauliai) Šiaul

- Page 887 and 888:

De Bilt (Prov. Utrecht): Cultureel

- Page 889 and 890:

Ijmuiden (Prov. Noord-Holland): Lib

- Page 891 and 892:

Rotterdam-Pendrecht (Prov. Zuid-Hol

- Page 893 and 894:

Halden-Remmen (Fylke Østfold) Univ

- Page 895 and 896:

Terceira see: Ílha Terceira Viana

- Page 897 and 898:

Blanca (Communidad de Autónoma Reg

- Page 899 and 900:

Santiago di Compostela-San Lázaro

- Page 901 and 902:

Luzern (Kanton Luzern) Bourbaki Pan

- Page 903 and 904:

Cambridge (Country England, Reg. Ea

- Page 905 and 906:

London (Country England, Reg. Londo

- Page 907 and 908:

Nottingham (Country England, Reg. E

- Page 909 and 910:

Anchorage-Girdwood (State Alaska, B

- Page 911 and 912:

Boston (State Massachusetts, County

- Page 913 and 914:

Charlottesville (State Virginia, Co

- Page 915 and 916:

Dallas (State Texas, County Dallas,

- Page 917 and 918:

Fayetteville (State Arkansas, Count

- Page 919 and 920:

Hobbs (State New Mexico, County Lea

- Page 921 and 922:

Litchfield (State Connecticut, Coun

- Page 923 and 924:

Middlebury (State Vermont, County A

- Page 925 and 926:

New York (State New York, Borough o

- Page 927 and 928:

New York (State New York, Borough o

- Page 929 and 930:

Phoenix (State Arizona, County Mari

- Page 931 and 932:

Richmond (State Virginia, County Ri

- Page 933 and 934:

San José (State California, County

- Page 935 and 936:

St. Louis (State Missouri, Independ

- Page 937 and 938:

Wakefield (State Massachusetts, Cou